On Wednesday, the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NHCS) released a major report on deaths from Long COVID. To identify a small (but significant) number of deaths, NCHS researchers searched through the text of death certificates for Long COVID-related terms. Their study demonstrates how bad our current health data systems are at capturing the results of chronic disease.

My colleagues and I at MuckRock did a similar analysis to the CDC’s, searching death certificate data that we received through public records requests and partnerships in Minnesota, New Mexico, and counties in California and Illinois. You can read our full story here and explore the death certificate data we analyzed on GitHub.

Here are the main findings from both analyses:

- The CDC study is an important milestone in recognizing the reality of Long COVID: this is a serious, chronic disease that can lead to death for some patients. It’s not just an outcome of acute COVID-19.

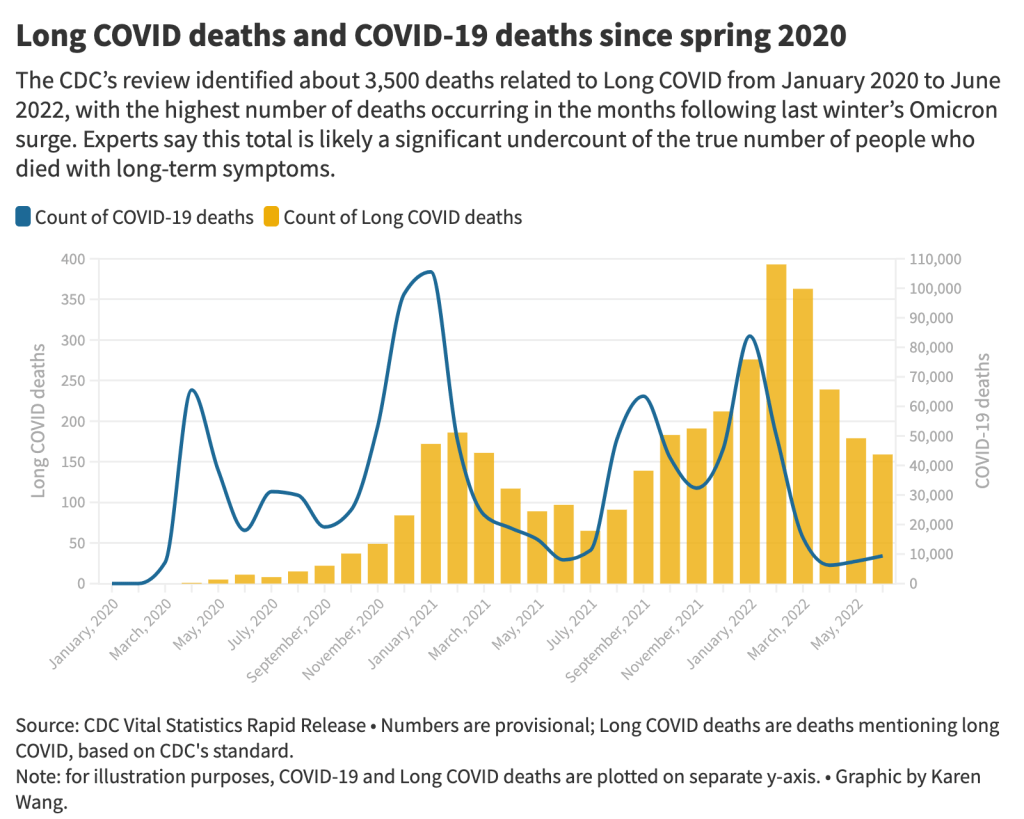

- From its national death certificate search, NCHS identified 3,544 deaths with Long COVID as a cause or contributing factor. This is almost certainly a major undercount, experts told me (and told other reporters who wrote about the study.)

- This number is an undercount because we’re essentially seeing two poor-quality data systems intersect. Long COVID is undercounted in clinical settings because we lack standard diagnostic tools and widespread medical education about it—most doctors wouldn’t think to put it on a death certificate as a result. And the U.S.’s death investigation system is uneven and under-resourced, leading to inconsistencies in tracking even well-known medical conditions.

- On top of these problems, when Long COVID is diagnosed, it tends to be among people who had severe cases of acute COVID-19 followed by difficulty recovering, experts told me. David Putrino and Ziyad Al-Aly, two leading Long COVID researchers, both pointed to the NCHS’s trend towards identifying Long COVID deaths among older adults (over age 75) as an example of this pattern in action, since this group is at higher risk for more severe acute symptoms.

- The NCHS count of deaths thus misses Long COVID patients with symptoms similar to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), which often arises after a milder initial case. It also misses people who have vascular impacts from a COVID-19 case, like a premature heart attack or stroke months after infection—something Al-Aly and his team have studied in depth. And, crucially, the NCHS count misses people who died from suicide, after suffering from severe mental health consequences of Long COVID.

- While the NCHS count of Long COVID deaths is far too low to be accurate, the researchers did find more deaths as the pandemic went on—with the highest number in February 2022, following the first Omicron surge. This pattern could suggest increased recognition of Long COVID among the medical community.

- The NCHS primarily identified Long COVID deaths among white people, even though acute COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted people of color in the U.S. Experts say this mismatch could reflect gaps in access to a diagnosis and care for Long COVID: if white people are more likely to be seen by a doctor who can accurately diagnose them, they will be overrepresented in Long COVID datasets. Putrino called this “a health disparity on top of a health disparity.”

- MuckRock’s analysis of death certificate data in select states similarly found that most deaths labeled as Long COVID were among seniors and white people. The trends varied by state, though, reflecting differences in populations and in local death reporting systems. For example in New Mexico, which has a statewide medical examiner’s office (rather than a looser system of county coroners), three-fourths of the Long COVID deaths were among Hispanic or Indigenous Americans.

- Our story also includes details about the RECOVER initiative’s autopsy study, which aims to use extensive postmortem testing on people who might have died from acute COVID-19 or Long COVID to identify biological patterns. Like the rest of RECOVER, this study is moving slowly and facing logistical challenges: about 85 patients have been enrolled so far, an investigator at New York University said.

Overall, the NCHS study suggests an urgent need for more medical education about Long COVID, especially as the CDC works to implement a new death code specific to this chronic condition. We also need broader outreach about the consequences of Long COVID. To quote from the story:

“Institutions like the CDC should do more to educate people about the long-term problems that could follow a COVID-19 case, said Hannah Davis, the patient researcher. “We need public warnings about risks of heart attack, stroke and other clotting conditions, especially in the first few months after COVID-19 infection,” she said, along with warnings about potential links to conditions like diabetes, Alzheimer’s and cancer.

And we need other methods of studying Long COVID outcomes that don’t rely on a deeply flawed death investigation system. These could include studies of excess mortality following COVID-19 cases, Long COVID patient registries that monitor people long-term, and collaborations with patient groups to track suicides.

For any reporters and editors who may be interested, MuckRock’s story is free for other outlets to republish.