- CDC Variant Proportions: The CDC has adjusted the update schedule of its variant proportions estimates, from every two weeks to once a week. Variant numbers are still somewhat delayed (the most recent estimates are now from August 7, about a week ago), but this is a big improvement. The agency has also expanded its estimates to include Delta sub-lineages, called AY.1, AY.2, and AY.3.

- COVID-19 Vaccination among People with Disabilities: Another recent change to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker is this new page, reflecting vaccination coverage among Americans with disabilities. Data come from the Census’ Household Pulse Survey, which began asking respondents about their disability and vaccine status in April 2021.

- Breakthrough cases by state, NYT: The New York Times has compiled and analyzed state data from on breakthrough (post-full-vaccination) COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths. This information is available for 40 states and Washington, D.C.; the remaining 10 states failed to share their data with the NYT. Raw data underlying this analysis have yet to be made public on the NYT GitHub repository.

- Education Stabilization Fund: The U.S. Department of Education has distributed a lot of money to school districts in the past year and a half—funding technology for remote learning, ventilation updates to buildings, COVID-19 tests, and more. This DOE database provides detailed records on which schools received funding and how much of the money has been spent.

Tag: breakthrough cases

-

Featured sources, August 15

-

A dispatch from Provincetown, Mass.

Provincetown in June 2006. Source: ingawh via Wikimedia Commons Last week, a COVID-19 outbreak in Cape Code, Massachusetts was revealed to be the subject of a major CDC study providing evidence of the Delta variant’s ability to spread through vaccinated individuals. The outbreak quickly became the subject of national headlines, many of them sensationalizing Delta’s breakthrough potential—while failing to provide much context on the people who actually got sick.

Here’s one big piece of context. Provincetown, the center of this outbreak, is one of America’s best-known gay communities, and the outbreak took place during Bear Week. Bear Week, for the uninitiated, is a week of parties for gay, bisexual, and otherwise men-loving men who identify as bears—a slang term implying a more masculine appearance, often facial and body hair.

This week, I had the opportunity to talk to Mike, a Bear Week attendee from Pittsburgh who caught COVID-19 in Provincetown. (Mike asked me to use only his first name to protect his privacy.) He told me about his experience attending parties, getting sick, and learning about the scale of the outbreak.

We also discussed how Provincetown and the Bear Week community were uniquely poised to identify this outbreak, thanks to a better-than-average local public health department and a group of men who were willing to share their health information with officials.

The interview below has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Betsy Ladyzhets: My first question is just like, how are you doing? How have you been after being involved in this outbreak?

Mike: I’m good… I live in Pittsburgh, I drove back on that Saturday [after the week of Provincetown events] and on Sunday, I started coughing really bad as I was driving home. This just came out of nowhere. I had to pull over, I’m like, yeah, I’m not good. This cough was a lot worse than I had anticipated. So, that was my first symptom. I went into the office Monday after getting home… My first test was negative, on like Monday or Tuesday. But like, I’m still coughing. I didn’t fully trust it. So I got another one Friday, a PCR test.

BL: So, you got tested twice? Did you experience contact tracing, or how did you get identified as part of the outbreak?

M: I mean, I just knew I’d been there. Um, no one reached out but… There was a Facebook group, probably ten or fifteen thousand people in it. Lots of people posted about their test results. Like, people after they were leaving [Provincetown], started quarantining.

The thing about Provincetown is, there were events that happened in the first week [of July, for July 4] that no one really had time to process… Then Bear Week, the week I went, I went at the busiest week of the year for the town. And it had to be, from a planning perspective, I don’t know that was necessarily the best time to have two huge events back to back.

All the official events for the week that I went were canceled, though there were some of the regular bars and stuff doing events. There was, at the time, I think one venue that has a mostly outdoor party every day from like three to seven, that was very heavily attended with one or two thousand people every day, mostly outside and it’s possible to distance at. I only ended up going once or twice just because it wasn’t really where I wanted to be regardless of COVID risks, it wasn’t particularly a scene that I was craving at the time.

I only went to, maybe, three or four indoor things the whole time, and it was without a mask for two or three of them. There’s a bunch of nightclubs in Provincetown that were still having events. And I don’t think that any of the bars themselves that were having events were requiring vaccination cards or anything. One venue that I saw a show at, they announced the next day that they were making either masks or proof of vaccination required. One of the venues that has outdoor events, they just moved all their shows outside instead of inside.

BL: I see. And you mentioned the Facebook group, was that how you found out that a lot of people were getting tested and things like that?

M: Yeah, there were somewhere between ten and fifteen thousand people in the group, planning this whole week. People usually come to Provincetown from all over, sometimes from abroad, though I don’t think there were many people coming from abroad this year because of the restrictions.

BL: How did you learn about the big CDC study getting written about this?

ML: I didn’t really have any idea until afterwards. There were lots of people in the group saying that Barnstable County, or the Massachusetts Department of Health, wanted to know—they wanted people to call if they’d gotten a positive test so they could keep better track of it. I mean, I think part of why the report was able to happen was that it was in a place with better respect for public health than, like, the state of Florida would have, if this kind of outbreak would’ve happened there.

B: Yeah, I mean, it definitely seems like they responded quickly. Because I know they had, like, a 15% positivity rate one week, and then within a pretty short time it was back down.

M: The town itself is a mostly gay, retirement-somewhat community. They can spend lots of money on other things [like public health]. They’re not necessarily spending money on schools because of how many people don’t have any kids around that they need to spend money on. And I mean, there are a lot of residents who live there year-round who tend to be older and are at more risk.

So the week [Bear Week] itself is unique, and then there was a huge community presence about it, everyone wanted to be—for the most part, we’re comfortable about reporting afterwards. I don’t think anyone knew, walking into this, what it would lead to, but… there’s a feeling of community, and that ten thousand-ish Facebook group, I don’t think we otherwise would have necessary talked to each other or told each other about Massachusetts [public health department] asking people to call if they were positive.

BL: And did you do that? Did you call them?

M: Um, I personally didn’t, since I didn’t even find out I was positive until a few days later.

BL: Now, as you know, this outbreak has gotten a lot of national coverage, it’s been kind of sensationalized, with a lot of people focusing on the vaccine breakthrough cases and stuff like that. I know you were not personally one of the people whose test measurements are included there. But what is that experience like of being part of this thing that has gotten so much national attention?

M: I posted about it on social media and there were lots of people who were surprised or whatnot. I think, at least in my head, I went in with a calculated risk, of like 10, 20, 30, or more in the ten thousand-ish people coming, a lot of them are traveling on planes. I drove, thinking I’ll come into this place and I think I’ll make okay decisions…

And there were people in this one place for a whole week, that I guess you were able to test from the CDC’s perspective. I don’t think there are many other places that are as remote as Provincetown where people are staying for the entire week, and everyone generally leaves on the same day, and everyone was in conversation with one another, talking about what happened.

Related links

- I Was Part of the July Fourth Provincetown “Breakthrough” COVID Cluster. It’s Been a Sobering Experience. (Slate)

- How A Gay Community Helped The CDC Spot A COVID Outbreak — And Learn More About Delta (NPR)

- How major media outlets screwed up the vaccine ‘breakthrough’ story (Columbia Journalism Review)

- Latest and greatest on Delta among vaccinated (Your Local Epidemiologist)

-

Featured sources, August 1

- State-by-state vaccination trends from the CDC: The CDC’s COVID Data Tracker has a new feature, added on July 29: you can now see vaccination trends for every state. On the Vaccination Trends page, use the “Select a Location” dropdown menu to pick a specific state or territory, then check out day-by-day numbers and rolling averages for doses administered and people newly vaccinated in that region. You can also download the state’s time series data from a table underneath the chart.

- COVID-19 Vaccine Breakthrough Cases: Data from the States (KFF): Looking to see how your state reports vaccine breakthrough cases? The Kaiser Family Foundation has you covered with this dashboard, including data and annotations from every state that reports breakthroughs. This resource was published on July 30; it’s unclear whether KFF intends to update it in the coming weeks.

- Poverty and Access to Internet, by County: Internet access has been a major issue during the pandemic as workplaces and schools have gone remote. This newly-updated dataset from the HHS Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality provides information on internet and cellular access in every U.S. county from 2014 to 2018.

-

Breakthrough case reporting: Once again, outside researchers do the CDC’s job

In May, the CDC switched from tracking and reporting all cases that occur in vaccinated Americans to reporting only those that cause hospitalizations or deaths. At the time, I criticized this move as a lazy choice that left the U.S. without critical information as Delta and other variants spread through the country.

Now, Delta is causing the vast majority of cases—and the CDC still isn’t reporting on non-severe breakthroughs. As a result, entities outside the federal government are once again compiling data from states in order to fill in gaps left by the national public health agency.

On Friday, both Bloomberg and NBC published breakthrough case analyses. Bloomberg reported 112,000 total breakthrough cases from 35 states, as of the end of July. This is a tiny fraction of the vaccinated population—over 164 million Americans—but it is far higher than the national breakthrough case number reported by the CDC in May, pre-reporting switch.

Bloomberg’s report includes plenty of expert critiques of the CDC’s May decision, suggesting that the lack of data led to many local public health officials flying blind as Delta spread.

With better understanding of how delta spreads, different public health measures or warnings could have been put in place for vaccinated people, said Rachael Piltch-Loeb, a Harvard Chan School of Public Health researcher on public health emergency responses.

According to NBC, America’s breakthrough case total is even higher: at least 125,000 cases from 38 states. Nine states, including Pennsylvania and Missouri, failed to provide NBC with any breakthrough case information, while 11 did not provide death and hospitalization numbers. Still, these cases have clearly increased substantially in the past two months, NBC reports:

In Utah on June 2, 2021, just 27 or 8 percent of the 312 new cases in the state were breakthrough cases. As of July 26 there were 519 new cases and almost 20 percent or 94 were breakthroughs, according to state data.

Now, it’s important to emphasize that breakthrough cases are still very rare and very mild, compared with non-breakthrough COVID-19. The 125,000 cases reported by NBC comprise less than 0.08% of the 164 million Americans who’ve been fully vaccinated. And the CDC reports just 6,600 severe breakthrough cases (leading to hospitalization and/or death) as of July 26.

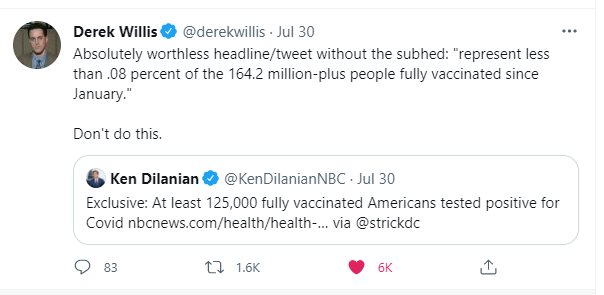

Any news article, headline, or tweet about breakthroughs should make that denominator explicitly clear—something that one NBC reporter failed to do when sharing his outlet’s story on Friday.

Also on Friday, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) published detailed annotations on state breakthrough case reporting. 24 states and D.C. have provided public data on this topic, according to KFF; some are reporting data regularly, while others have included the information in limited press releases and other reports.

If your state is one of the 26 states not providing any public breakthrough case data at all, I’d recommend reaching out to the state public health agency and asking why not. Yes, it’s challenging to identify these cases when vaccinated people tend to have mild symptoms and might not think to get a test. And yes, the vast majority of people who have a breakthrough case will likely be fine in a couple of weeks. But the information is vital as Delta continues to wreak havoc across the country.

More vaccine reporting

- Sources and updates, November 12Sources and updates for the week of November 12 include new vaccination data, a rapid test receiving FDA approval, treatment guidelines, and more.

- How is the CDC tracking the latest round of COVID-19 vaccines?Following the end of the federal public health emergency in May, the CDC has lost its authority to collect vaccination data from all state and local health agencies that keep immunization records. As a result, the CDC is no longer providing comprehensive vaccination numbers on its COVID-19 dashboards. But we still have some information about this year’s vaccination campaign, thanks to continued CDC efforts as well as reporting by other health agencies and research organizations.

- Sources and updates, October 8Sources and updates for the week of October 8 include new papers about booster shot uptake, at-home tests, and Long COVID symptoms.

- COVID source shout-out: Novavax’s booster is now availableThis week, the FDA authorized Novavax’s updated COVID-19 vaccine. Here’s why some people are excited to get Novavax’s vaccine this fall, as opposed to Pfizer’s or Moderna’s.

- COVID-19 vaccine issues: Stories from COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers across the U.S.Last week, I asked you, COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers, to send me your stories of challenges you experienced when trying to get this fall’s COVID-19 vaccines. I received 35 responses from readers across the country, demonstrating issues with insurance coverage, pharmacy logistics, and more.

- Sources and updates, November 12

-

Breakthrough cases: What we know right now

Washington is one of the states reporting high levels of detail about breakthrough cases. Screenshot via June 23 report. For the past few months, we’ve been watching the vaccines and variants race in real time. With every new case, the coronavirus has the opportunity to mutate—and many scientists agree that it will inevitably mutate into a viral variant capable of outsmarting our current vaccines.

How will we know when that happens? Through genomic surveillance, examining the structure of coronavirus lineages that arise in the U.S. and globally. While epidemiologists may consider any new outbreak a possible source of new variants, one key way to monitor the virus/variant race is by analyzing breakthrough cases—those infections that occur after someone has been fully vaccinated.

In May, the CDC changed how it tracks breakthrough cases: the agency now only investigates and reports those breakthrough cases that result in hospitalizations or deaths. I wrote about this in May, but a new analysis from COVID Tracking Project alums and the Rockefeller Foundation provides more detail on the situation.

A couple of highlights from this new analysis:

- 15 states regularly report some degree of information about vaccine breakthroughs, some including hospitalizations and deaths.

- Six states report sequencing results identifying viral lineages of their breakthrough cases: Nebraska, Arkansas, Alaska, Montana, Oregon, and Washington.

- Washington and Oregon are unique in providing limited demographic data about their breakthrough cases.

- Several more states have reported breakthrough cases in isolated press briefings or media reports, rather than including this vital information in regular reports or on dashboards.

- When the CDC stopped reporting breakthrough infections that did not result in severe disease, the number of breakthrough cases reported dropped dramatically.

- We need more data collection and reporting about these cases, on both state and federal levels. Better coordination between healthcare facilities, laboratories, and public health agencies would help.

Vaccine breakthrough cases are kind-of a data black box right now. We don’t know exactly how many are happening, where they are, or—most importantly—which variants they’re tied to. The Rockefeller Foundation is working to increase global collaboration for genomic sequencing and data sharing via a new Pandemic Prevention Institute.

Luckily, there is a lot we do know from another side of the vaccine/variant race: vaccine studies have consistently brought good news about how well our current vaccines work against variants. The mRNA vaccines in particular are highly effective, especially after one has completed a two-dose regimen. If you’d like more details, watch Dr. Anthony Fauci in Thursday’s White House COVID-19 briefing, starting about 14 minutes in.

New research, out this week, confirmed that even the one-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine works well against the Delta variant. The company reported that, after a patient receives this vaccine, blood antibody levels are high enough to beat off an infection from Delta. In other words, people who got the J&J shot do not need to rush to get a booster shot from an mRNA vaccine (a recent debate topic among some experts).

Again, we’ll need more genomic surveillance to carefully watch for the variant that inevitably does beat our vaccines. But for now, the vaccinated are safe from variants—and getting vaccinated remains the top protection for those who aren’t yet.

More variant reporting

-

Why did the CDC change its breakthrough case reporting?

Earlier this month, the CDC made a pretty significant change in how it tracks breakthrough cases. Instead of reporting all cases, the agency is only investigating and collecting data on those cases that result in hospitalizations or deaths.

In case you need a refresher: “breakthrough cases” are those infections that occur after a patient is fully vaccinated (including both doses, if applicable, and the two-week waiting period after a final dose). These cases are rare—like, one in ten thousand rare. As I wrote back in April, it’s important to contextualize any reporting on these cases with their incredible rareness so that we hammer home just how effective the vaccines are.

But just because breakthrough cases are rare doesn’t mean we shouldn’t pay attention to them. In fact, it’s critical to pay attention to these cases in order to monitor precisely how well our vaccines are working—and how new variants may threaten the protections those vaccines provide.

As The Atlantic’s Katherine J. Wu explains:

Breakthroughs can offer a unique wellspring of data. Ferreting them out will help researchers confirm the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines, detect coronavirus variants that could evade our immune defenses, and estimate when we might need our next round of shots—if we do at all.

As I’ve discussed in past variant reporting, numerous studies have demonstrated that the vaccines currently in use in the U.S.—especially the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines—work well against all variants. That includes variants of concern, such as B.1.617 (from India), B.1.351 (from South Africa), and P.1 (from Brazil). But the vaccine efficacy rates for some of these variants are lower than that stellar 95% we saw in Pfizer and Moderna’s clinical trials. And some common therapeutic drugs don’t work well for patients infected with variants, too.

As a result, scientists are concerned that, while the vaccines are working well now, they might not work well forever. Whenever the coronavirus infects a new person, it has the opportunity to evolve. And that continued evolution must be monitored. The first coronavirus variant able to evade our vaccines may emerge in a foreign country with a raging outbreak—but it may also emerge here in the U.S. Closely monitoring all breakthrough cases will help us find that dangerous variant.

(Of note: A new, potentially-concerning variant was identified just last night in Vietnam; WHO scientist Maria Van Kerkhove described it as an offshoot of the variant from India, B.1.617, with “additional mutation(s).”)

With that in mind, let’s unpack the CDC’s reporting change. When the vaccine rollout started, the agency was investigating all breakthrough cases that came to its attention—including those in patients with only mild symptoms, or with no symptoms at all. According to an agency study released this past Tuesday, the CDC identified 10,262 such breakthrough cases from 46 U.S. states and territories between January 1 and April 30, 2021.

Keep in mind: By April 30, about 108 million Americans had been fully vaccinated. Dividing 10,262 by 108 million is where I got that “one in ten thousand” comparison I cited earlier. As I said: very rare.

Starting on May 1, however, the CDC changed its strategy. Now, it is only tracking breakthrough cases that result in severe illness for patients, leading to hospitalization and/or death. The CDC says that this choice is intended to focus on “the cases of highest clinical and public health significance” rather than tracking down asymptomatic cases.

In its May 25 report, CDC scientists said that 27% of the breakthrough cases identified before May 1 were asymptomatic. 10% of the infected individuals were hospitalized, though almost a third of those patients were hospitalized for a reason unrelated to COVID-19. Only 160 patients (less than 2% of the breakthrough cases) died.

We need to take these numbers with a grain of salt, though, because the CDC has likely undercounted the true number of asymptomatic cases. Both clinical trials and studies on vaccine effectiveness in the real world have suggested that those people who get infected with COVID-19 after completing a vaccination regime are more likely to have mild symptoms, or no symptoms at all.

Plus, the CDC is recommending that vaccinated Americans don’t need to get tested before traveling, if they have come into contact with someone known to have COVID-19, or for many of the other reasons that many of us got tested this past year. (The agency is still recommending that fully vaccinated people get tested if they’re experiencing COVID-19 symptoms, though.)

As I wrote at Slate Future Tense last month, such guidelines are likely to drive down the number of COVID-19 tests conducted across the U.S. And this trend seems to be happening, so far: PCR tests dropped from their winter surge levels this spring, and are now dropping again. (Antigen and other rapid tests may be getting used more, but we don’t have any comprehensive data on them.)

With that drop in testing—combined with the overall challenge of identifying asymptomatic COVID-19 cases outside of dedicated studies—it would be pretty damn hard for the CDC to track down all breakthrough cases. The agency’s focus on more serious cases instead may thus be considered a conservation of resources, directing research efforts and care to those Americans who get seriously ill after vaccination.

But “a conservation of resources” is also a nice way of saying, the CDC made a lazy choice here. The agency has poured money into genomic surveillance over the past few months, sequencing over 20,000 cases a week (compared to a few thousand cases a week before Biden took office). In recent weeks, the Biden administration has announced renewed funding for public health and similar commitments to prioritizing scientific research. If the CDC wants to find and sequence breakthrough cases in order to identify vaccine-busting variants, there should be nothing stopping the agency.

Or, as epidemiologist Dr. Ali Mokdad told the New York Times: “The C.D.C. is a surveillance agency. How can you do surveillance and pick one number and not look at the whole?”

Out of those 10,262 cases that the CDC reported this week, only 5% had sequence data available—but the majority of those sequined cases were variants of concern, including B.1.1.7 and P.1. At The Atlantic, Wu reported that epidemiologists in some parts of the country are seeing more breakthrough cases tied to concerning variants, while others are seeing breakthrough case sequences that match the overall infections in the community.

To me, this high level of unknowns and uncertainties mean that we need more breakthrough case reporting and sequencing, not less. And we need a national public health agency that commits to true surveillance, so that we aren’t flying blind when the coronavirus inevitably evolves beyond our current defenses.

(P.S. Shout-out to Illinois, the one state that reports its own breakthrough case data.)

More vaccine reporting

- Sources and updates, November 12Sources and updates for the week of November 12 include new vaccination data, a rapid test receiving FDA approval, treatment guidelines, and more.

- How is the CDC tracking the latest round of COVID-19 vaccines?Following the end of the federal public health emergency in May, the CDC has lost its authority to collect vaccination data from all state and local health agencies that keep immunization records. As a result, the CDC is no longer providing comprehensive vaccination numbers on its COVID-19 dashboards. But we still have some information about this year’s vaccination campaign, thanks to continued CDC efforts as well as reporting by other health agencies and research organizations.

- Sources and updates, October 8Sources and updates for the week of October 8 include new papers about booster shot uptake, at-home tests, and Long COVID symptoms.

- COVID source shout-out: Novavax’s booster is now availableThis week, the FDA authorized Novavax’s updated COVID-19 vaccine. Here’s why some people are excited to get Novavax’s vaccine this fall, as opposed to Pfizer’s or Moderna’s.

- COVID-19 vaccine issues: Stories from COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers across the U.S.Last week, I asked you, COVID-19 Data Dispatch readers, to send me your stories of challenges you experienced when trying to get this fall’s COVID-19 vaccines. I received 35 responses from readers across the country, demonstrating issues with insurance coverage, pharmacy logistics, and more.

- Sources and updates, November 12

-

How to talk about breakthrough cases

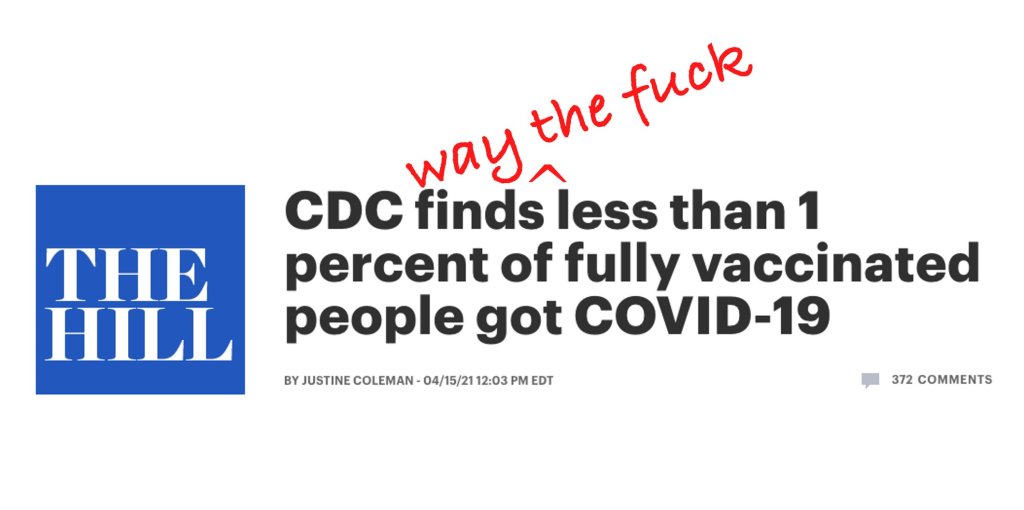

This week, The Hill posted an article with a rather misleading headline: “CDC finds less than 1 percent of fully vaccinated people got COVID-19.” If you actually click into the piece, you’ll find that the precise number is less than 0.008%. Less than 0.0005% have been hospitalized and less than 0.0001% have died.

This headline reflects a common issue with vaccine reporting that I’ve seen in the past few weeks. A lot of journalists, especially those who aren’t familiar with the science/health beat, may be inclined to publish news of breakthrough cases as surprising or monumental. In fact, these cases—referring to a COVID-19 infection that occurs after someone has been fully vaccinated—are entirely normal, yet incredibly rare.

No vaccine is perfect. Even the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, which both demonstrated 95% efficacy in their late-stage clinical trials and over 90% effectiveness in the real world, are not perfect. Scientists still expect a few COVID-19 infections to slip through the immune system defenses built up by these vaccines and cause illness in a small number of patients.

And it really is a small number: 129 million Americans have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine as of yesterday, per the CDC, and 82 million have been fully vaccinated. The agency has only documented 5,800 breakthrough cases. Less than 0.008% of those people who have been fully vaccinated. That’s the equivalent of one-quarter of a seat in Queens’ Citi Field baseball stadium (which seats about 42,000).

So, if you’re a journalist reporting on this issue—whether it’s nationally or in your community—it’s important to stress that denominator. 82 million fully vaccinated, 5,800 breakthrough cases. Emphasizing the difference in magnitude between these numbers can show readers that, while they should still maintain some caution after getting vaccinated, the vaccines are overwhelmingly safe and effective.

Small as the breakthrough case numbers are, though, it is important that we still talk about them. A new article by ProPublica’s Caroline Chen discusses how a failure to collect data on breakthrough cases is making it harder for COVID-19 researchers to understand what causes them. Specifically: we should be sequencing the genomes of the coronavirus strains that caused these cases, and by and large, we aren’t.

Chen describes how many state health departments aren’t getting breakthrough case samples to sequence, whether that’s due to testing labs failing to store the test samples or cases being identified through rapid tests, which do not have established pipelines. Plus, in some cases, we aren’t even recording whether the patients went to the hospital or died—key data points in the U.S.’s continued vaccine monitoring.

I definitely recommend you read the full piece, but here’s a section that will give you the big idea:

In many instances, patients’ samples are not sequenced to find out if a variant might have been involved; some labs are throwing out test samples before an analysis can be done; hospitals and clinics aren’t always collecting new samples to analyze them. That means that for so many people, nobody will ever know if a variant was involved, leaving public health officials without data to be able to examine the extent to which variants are contributing to breakthrough cases.

“It’s alarming that we can’t sequence more of the virus than we’re able to now — that’s something we need to resolve,” said Brian Castrucci, chief executive officer at the de Beaumont Foundation, a health philanthropy. “The more we know, the better we can react. We want to know the information so that we can make the right policy and health decisions.”

While the CDC has an info page on breakthrough cases, no data on these cases are available on the agency’s COVID-19 dashboard. Reporters need to walk a delicate line on this issue: pursue the data, but report it in a careful, conscientious way that appropriately puts the tiny breakthrough case numbers in context.

More vaccine news

- Sources and updates, November 12Sources and updates for the week of November 12 include new vaccination data, a rapid test receiving FDA approval, treatment guidelines, and more.

- How is the CDC tracking the latest round of COVID-19 vaccines?Following the end of the federal public health emergency in May, the CDC has lost its authority to collect vaccination data from all state and local health agencies that keep immunization records. As a result, the CDC is no longer providing comprehensive vaccination numbers on its COVID-19 dashboards. But we still have some information about this year’s vaccination campaign, thanks to continued CDC efforts as well as reporting by other health agencies and research organizations.

- Sources and updates, October 8Sources and updates for the week of October 8 include new papers about booster shot uptake, at-home tests, and Long COVID symptoms.

- COVID source shout-out: Novavax’s booster is now availableThis week, the FDA authorized Novavax’s updated COVID-19 vaccine. Here’s why some people are excited to get Novavax’s vaccine this fall, as opposed to Pfizer’s or Moderna’s.

- Sources and updates, November 12