In the past week (October 13 through 19), the U.S. reported about 260,000 new COVID-19 cases, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 37,000 new cases each day

- 79 total new cases for every 100,000 Americans

- 2% fewer new cases than last week (October 6-12)

In the past week, the U.S. also reported about 22,000 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals. This amounts to:

- An average of 3,200 new admissions each day

- 6.7 total admissions for every 100,000 Americans

- 4% fewer new admissions than last week

Additionally, the U.S. reported:

- 2,600 new COVID-19 deaths (390 per day)

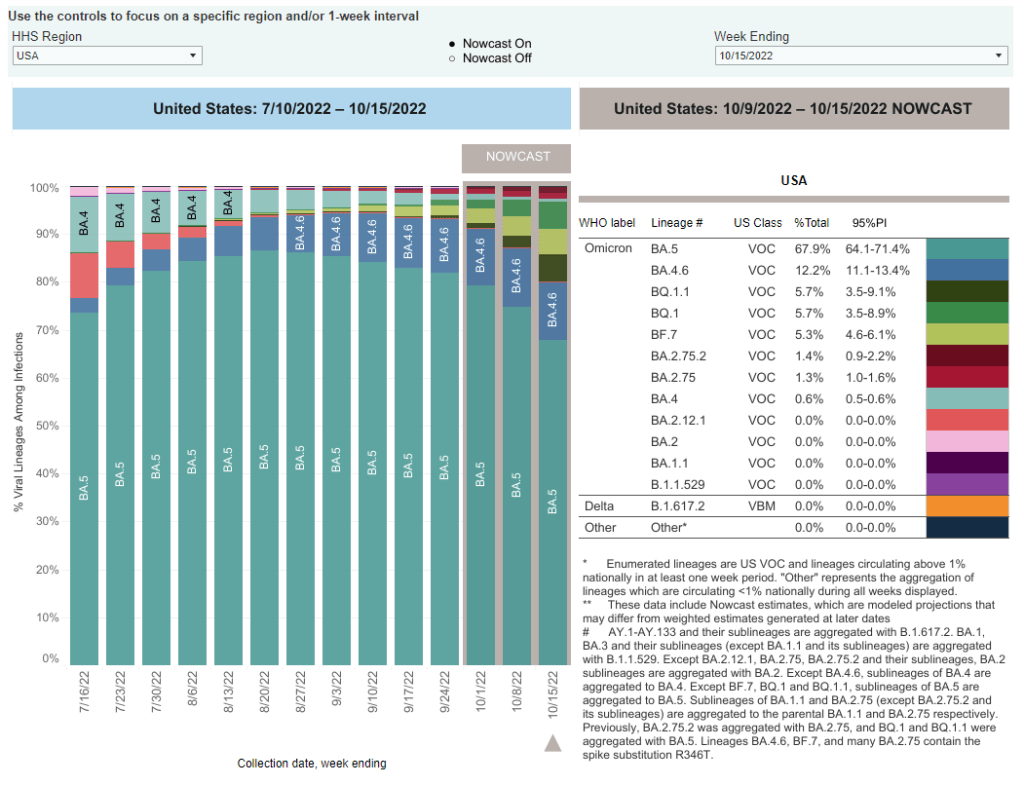

- 11% of new cases are caused by Omicron BA.4.6; 17% by BQ.1 and BQ.1.1; 7% by BF.7; 3% by BA.2.75 and BA.2.75.2 (as of October 22)

- An average of 400,000 vaccinations per day (CDC link)

Official COVID-19 case numbers continue to drop nationwide, according to the CDC, but I remain concerned that a fall surge is coming soon—if it isn’t already here.

As the CDC transitioned this week from daily to weekly case reporting (more on that later in the issue), the agency’s “COVID Data Tracker Weekly Review” report, which I use to write these posts, is now using three-week rolling averages for its trends instead of one-week averages. The three-week average suggests reported cases are down 30% in the last month. But the actual case numbers report a dip of just 1% from last week to this week, suggesting a plateau in cases.

Data from Biobot’s dashboard similarly suggest a plateau in nationwide transmission trends, with the Northeast reporting more viral transmission than other regions. The wastewater data suggest that, nationwide, coronavirus transmission is on a similar level to what it was in early fall last year, before Omicron arrived. But the case numbers are now much lower thanks to limited testing access.

Consider this: recent estimates from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation suggest only 4% to 5% of actual coronavirus infections make it into the public health system now. If this is correct, actual infection numbers in the U.S. are 20 times higher than our actual count, amounting to 740,000 true cases a day.

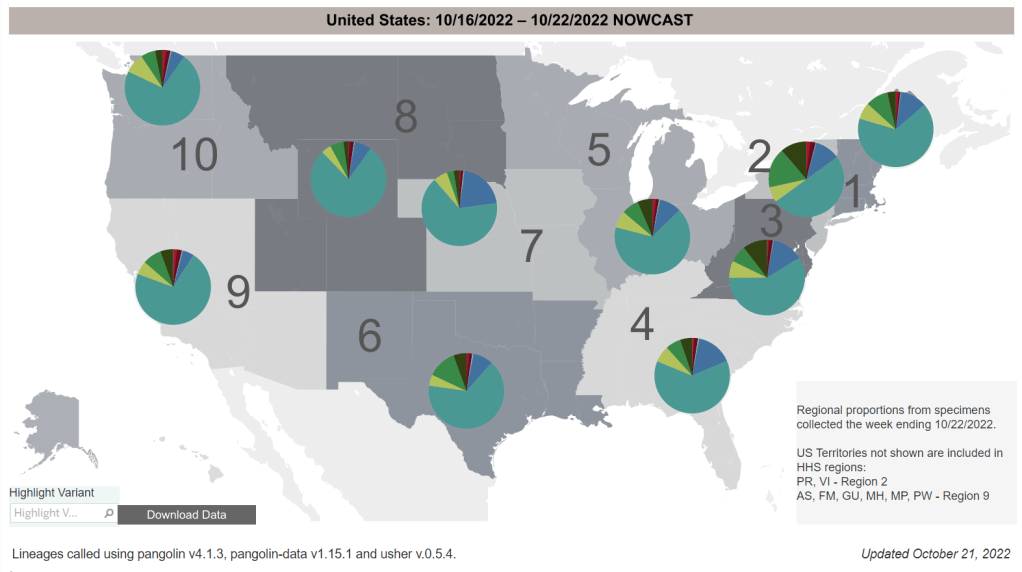

The Northeast remains a hotspot, as the first region to note signs of a new surge. Some New England cities and counties—including Boston—are seeing spikes or high plateaus in their coronavirus levels in wastewater, Biobot reports. States in this region, especially New York and New Jersey, report more BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 than other parts of the country; if new variants aren’t contributing yet to a surge, they will be soon.

Overall, BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 are now causing about one in six new cases in the U.S. and are anticipated to become dominant subvariants within a few weeks. This could have implications for treatments such as Evusheld, a monoclonal antibody drug for immunocompromised people. While the bivalent/Omicron-specific booster shots should still work against BQ.1 and BQ.1.1, uptake of these vaccines remains very low. (See last week’s post for more subvariant details.)