As of this Thursday, the CDC is updating COVID-19 case and death data every week instead of every day. Here are some thoughts on interpreting COVID-19 data in the wake of this change, citing an article I recently wrote for The Atlantic.

To me, the CDC’s shift to weekly updates feels like the end of an era for tracking COVID-19. While I understand the change, considering both our less-complete case information and other data analysis needs for the agency, I can’t help but wish we had a national public health agency with enough resources to continue providing us with frequent, reliable information on this ongoing pandemic. After all, shouldn’t that be the CDC’s job?

The CDC has clearly deprioritized two major metrics (cases and deaths) that used to be the first places people looked to see the pandemic’s impact on their communities. Instead, the agency now points us to hospitalization metrics, variant surveillance, and wastewater—all metrics that are certainly useful, but may be harder for the average user to interpret.

And even the case data we do have are quite unreliable at this point, as PCR tests become less and less accessible compared to rapid tests. Case numbers may be underreported by twenty times or more; it’s difficult to even get a good estimate of how far off the numbers are. Public communications like the CDC’s “Weekly Review” report fail to acknowledge this problem, and the agency does not appear to be making any effort to determine the true infection rates right now.

Through its current data communication choices, the CDC seems to be saying, “If you still care about keeping track of COVID-19, you’re on your own.” Even though we are likely heading for a fall surge and many people need to keep track of this disease in order to keep their communities safe.

In absence of useful information from our public health leaders, it falls on us to survey the best available data sources and help others interpret them. My article in The Atlantic takes on this question, focusing on wastewater surveillance and population surveys as particularly useful sources we should consider right now.

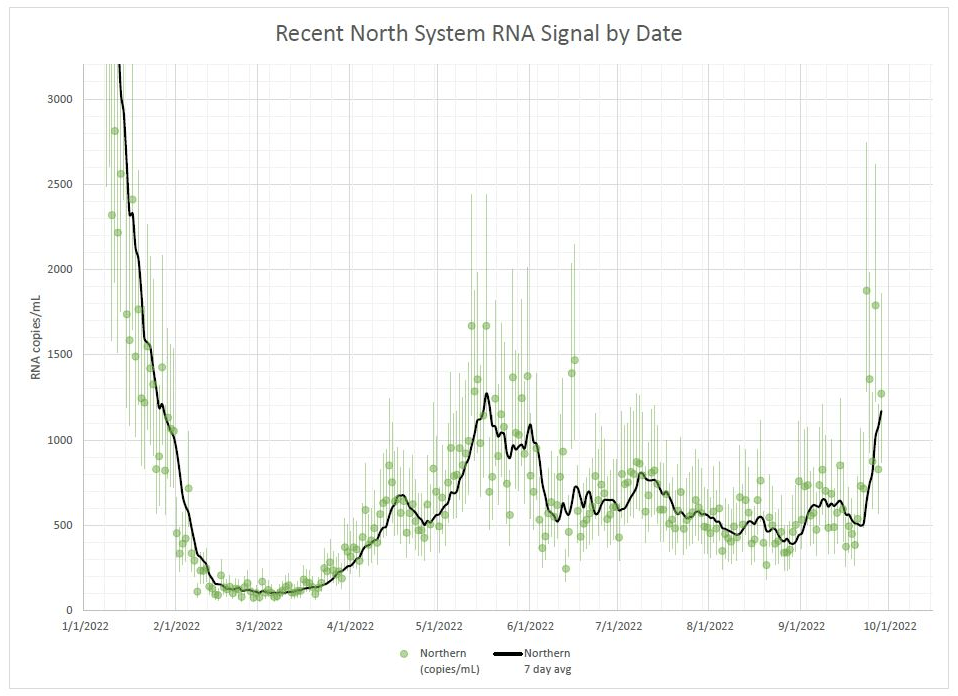

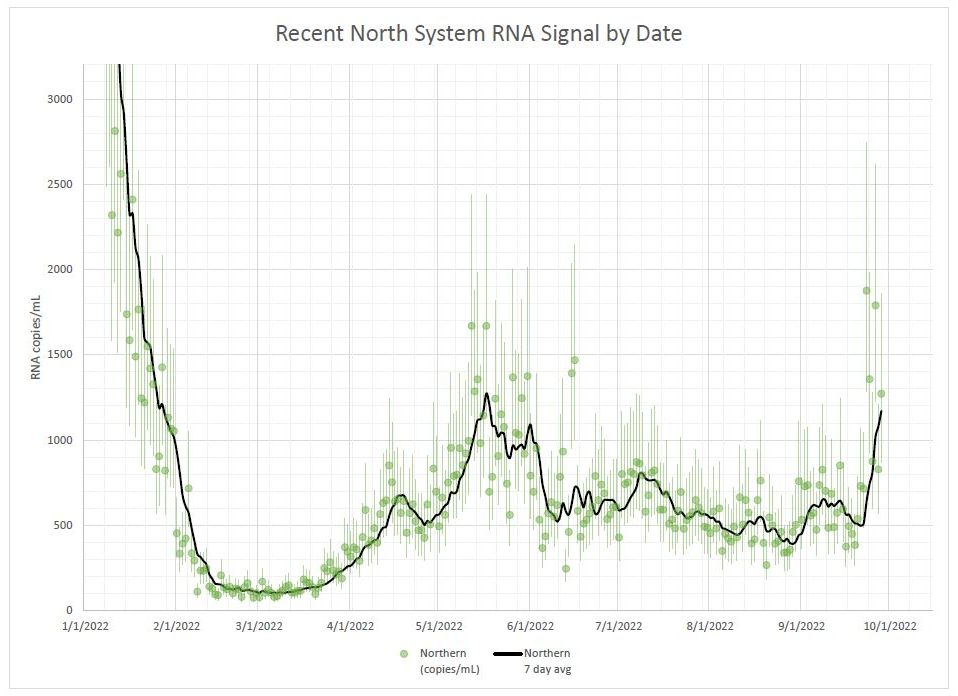

Interpreting wastewater data

Wastewater data, unlike case data, don’t require people to actively go out and get tested: if their public sewer system is getting sampled for COVID-19, they will automatically be included in the data. You can look for wastewater surveillance in your area on Biobot’s dashboard, the CDC’s dashboard, or other state and local dashboards, depending on where you live. (I have a list of state dashboards here.)

But interpreting wastewater data can be pretty different from interpreting case data. Here are a couple of key tips for approaching this source, based on my interview with Biobot president and cofounder Newsha Ghaeli:

- Look at “directionality” and “magnitude.” “Directionality” means whether viral levels are going up or down, and “magnitude” means how they compare with earlier points in the pandemic. To quote from the story: “A 10 percent uptick when levels are low is less concerning than a 10 percent uptick when the virus is already spreading widely.”

- If you do not have public wastewater data for your county, data from a neighboring county still provides useful info. When we talked, Ghaeli gave the example of a New York City resident looking at data from New Jersey or Connecticut counties neighboring the city: as people from these areas commute into NYC, a surge in one place could quickly drive a surge in the other.

- Wastewater data are not a perfect proxy for infections. Scientists are still learning about how to best use this newer surveillance tool. Unlike clinical metrics (like cases), wastewater data can differ based on local environmental factors, and it often takes a long time for researchers to build useful interpretations of their communities. (See my past FiveThirtyEight story for more detail on this.)

- These data can’t tell you who is getting sick. To comprehensively answer demographic questions, we need to actively survey people in our communities and ask them about their experiences with COVID-19. (See the story for more about how this works.)

Other interpretation tips

Beyond looking at wastewater data, here are a couple of tips I received from experts for readers seeking to watch their local COVID-19 numbers this fall:

- “Look as local as you can,” said Pandemic Prevention Initiative expert Sam Scarpino. In other words, if you can find data for your individual county or even ZIP code, go there.

- Check multiple sources, and try to “triangulate” between them, said City University of New York epidemiologist Denis Nash. (I’ve provided similar advice in past posts like this one.)

- Consider local events and behavior, Scarpino said. Quoting from the story: “If a popular community event or holiday happened recently, low case numbers might need to be taken with a grain of salt.”

I also wanted to give a quick shout-out here to the People’s CDC, a volunteer science communication and advocacy organization. If you’re looking for more thoughtful analysis of national COVID-19 data, their weekly “weather reports” are a really helpful and accessible source. The organization also provides resources to help people push for more COVID-19 safety measures in their communities.

“People do want layers of protection, they do want to keep themselves in each other safe from COVID,” said Mary Jirmanus Saba, a geographer and volunteer with the People’s CDC whom I interviewed (with a couple of other volunteers) for my story. The weather reports and other similar initiatives help the organization’s followers “see that we really are there for each other,” she said.