- Healthcare worker burnout trend backed up by new data: The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated a growing burnout crisis among healthcare workers in the U.S., as many articles and scientific papers have explored in the last couple of years. Two studies from the past week add more data to back up the trend. CDC researchers shared the results of a survey of about 2,000 workers, finding that workers were more likely to report poor mental health and burnout in 2022 than in 2018, while harassment and a lack of support at work contributed to increased burnout. Another research group (at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and Washington University in St. Louis) also surveyed healthcare workers and found that many experienced food insecurity and financial challenges; workers with worse employer benefits were more likely to increase these challenges.

- Viral load not necessarily associated with symptoms: This paper is a rare, relatively recent update on how COVID-19 symptoms connect to viral load, or the amount of virus that a patient has in their respiratory tract. The higher a patient’s viral load, the more likely they are to infect others, making this an important metric for contagiousness. Researchers at Emory University studied viral loads in about 350 people diagnosed with Omicron variants between April 2022 and April 2023. Patients tended to have their highest viral loads around the fourth day of symptoms, a change from studies done on earlier variants (when viral loads tended to peak along with symptoms starting). As Mara Aspinall and Liz Ruark explain in their testing newsletter, these results have implications for rapid at-home tests, which are most accurate when viral loads are high: if you’re symptomatic but negative on a rapid test, keep testing for several days, and consider isolating anyway.

- Updated vaccines are key for protection: Another recent paper, in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, examines how last year’s bivalent COVID-19 vaccines worked against recent coronavirus variants using data from the Kaiser Permanente health system. The study included records from about 123,000 people who had received at least the original vaccine series, examining health system visits from August 2022 to April 2023. People who received an updated vaccine in fall 2022 were significantly less likely to have severe COVID-19, the researchers found. “By mid-April, 2023, individuals previously vaccinated only with wild-type vaccines had little protection against COVID-19,” the researchers wrote. This year’s updated vaccine may have a similar impact through spring 2024.

- Gut fungi as a potential driver for Long COVID: Long COVID, like ME/CFS and other chronic conditions, may be associated with problems in patients’ gut microbiomes, i.e. the communities of microorganisms that live in our digestive systems. A new paper in Nature Immunology from researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine hones in on one fungal species that may be particularly good at causing problems. The species, Candida albicans, can grow in the intestines of severe COVID-19 and Long COVID patients, triggering to inflammation and other immune system issues. This paper describes results from patient samples as well as a mouse model mimicking how this fungal species grows in COVID-19 patients’ guts.

- Another potential Long COVID biomarker: One more notable Long COVID paper from this week: researchers at the University of Alberta studied blood samples from people with the condition, and compared their results to people who had acute COVID-19 but didn’t go on to develop long-term symptoms. The scientists used machine learning to develop a computer model differentiating between blood composition of people who did and didn’t develop Long COVID. They identified taurine as one specific amino acid that might be particularly important, as levels of taurine were lower among patients with more Long COVID symptoms. The study could be used to inform diagnostic tests of Long COVID, as well as potential treatments to restore taurine.

Tag: antigen tests

-

Sources and updates, October 29

-

Answering reader questions about wastewater data, rapid tests, Paxlovid

I wanted to highlight a couple of questions (and comments) that I’ve received recently from readers, hoping that they will be useful for others.

Interpreting wastewater surveillance data

One reader asked about how to interpret wastewater surveillance data, specifically looking at a California county on the WastewaterSCAN dashboard. She noticed that the dashboard includes both line charts (showing coronavirus trends over time) and heat maps (showing coronavirus levels), and asked: “I’m wondering what the difference is, and which is most relevant to following actual infection rates and trends?”

My response: Wastewater data can be messy because environmental factors can interfere with the results, and what may appear to be a trend may quickly change or reverse course (this FiveThirtyEight article I wrote last spring on the topic continues to be relevant). So a lot of dashboards use some kind of “risk level” metric in addition to showing linear trends in order to give users something a bit easier to interpret. See the “virus levels” categories on the CDC dashboard, for instance.

Personally, I like to look at trends over time to see if there might be an uptick in a particular location that I should worry about, but I find the risk level metrics to be more useful for actually following infection rates. Of course, every dashboard has its own process for calculating these levels—and we don’t yet have a good understanding of how wastewater data actually correlate to true community infections—so it’s helpful to also check out other metrics, like hospitalizations in your county.

Rapid test accuracy

Another reader asked: “Is there any data on the effectiveness of rapid tests for current variants like Arcturus? I’m hearing more and more that they are working less and less well as COVID evolves.”

My response: Unfortunately, I’m not aware of any specific data on rapid test effectiveness for recent variants. Early in the Omicron period, there were a few studies that showed the rapid tests still worked for that variant. The virus has obviously evolved a lot since then, but there is less interest in and fewer resources for evaluating these questions at this point in the pandemic, so it’s hard to say whether the continued mutations have had a significant impact on test effectiveness.

I think it’s important to flag, though, that rapid tests have never been highly accurate. People have tested negative on rapids—only to get a positive PCR the next day—since these tests were first introduced in spring 2021. The tests can be helpful for identifying if someone is contagious, with a high viral load, but are less accurate for people without symptoms. So, my recommendation with these tests is always to test multiple times, and to get a PCR if you have access to that. (Acknowledging there is less and less PCR access these days.) Also, if you were recently exposed to COVID-19, wait a few days to start rapid testing; see more details in this post from last year.

Double dose of Paxlovid

Another reader wrote in to share their experience with accessing Paxlovid during a recent COVID-19 case. The reader received a Paxlovid prescription, which led to a serious alleviation of symptoms. But when she experienced a rebound of symptoms after finishing the Paxlovid course, she had a hard time getting a second prescription.

“Fauci, Biden, head of Pfizer and CDC director got a second course of Paxlovid prescribed to them,” the reader wrote. “When I attempted to get this, my doctors pretended I was crazy and said this was never done.” She added that she’d like to publicize the two-course Paxlovid option.

My response: I appreciate this reader sharing her experience, and I hope others can consider getting multiple Paxlovid prescriptions for a COVID-19 case. The FDA just provided full approval to Pfizer for the drug, which should alleviate some bureaucratic hurdles to access. I also know that current clinical trials testing Paxlovid as a potential Long COVID treatment are using a longer course; 15 days rather than five days. The results of those trials may provide some evidence to support a longer course overall.

If you have a COVID-19 question, please send me an email and I’ll respond in a future issue!

-

COVID source shout-out: New NIH tool to report at-home test results

Make My Test Count is a new NIH website for people to report at-home COVID-19 test results. This week, the National Institutes of Health launched a new website that allows people to anonymously report their at-home test results. While I’m skeptical about how much useful data will actually result from the site, it could be a helpful tool to gauge how willing Americans are to self-report test results.

The website, MakeMyTestCount.org, puts users through a series of basic questions about their at-home test experience: your test result, the test brand you used, when you tested, and whether you have COVID-19 symptoms. The site also asks for basic demographic information, including your age, ZIP code, race, and ethnicity. After you report your test result, the website provides additional context on interpreting that result, such as suggesting a repeat test in the next two days if you have symptoms.

These survey questions mimic the information that typically gets collected when someone receives a PCR test, and the resulting data could potentially be used to examine who is using at-home tests and what their results are. The NIH’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (or RADx) initiative, a program to speed up development and use of COVID-19 testing technologies, designed the website.

Of course, there are a lot of potential issues here. This website was launched more than two years after the first COVID-19 rapid tests were authorized and almost one year after they gained widespread popularity during the first Omicron surge. No matter how many people report their results now, the NIH will miss a lot of data and a lot of opportunities to advertise the site.

And how many people will report their results now? Pandemic safety measures like at-home testing are less popular than they were a year ago, and the launch of this website doesn’t seem to be paired with a public outreach campaign about using and reporting at-home tests. Basically, the results shared with the NIH are likely to be biased towards people who still care about taking precautions (and those who pay attention to federal COVID-19 resources). It’s also very easy to submit false results, as the website doesn’t ask for a photo of your test or anything similar.

Still, I’m excited to see this website launched—collecting some at-home test results is better than no test results! I hope lots of people use it, and I look forward to seeing any data the NIH eventually releases from the tool.

-

Orders of free at-home COVID-19 tests varied widely by state

On September 2, 2022, the federal government stopped taking orders for free at-home COVID-19 tests. The distribution program, which launched during the first Omicron surge in early 2022, allowed households to order free tests up to three times, with either four or eight tests in each order.

The day this program ended, I sent a public records request to the federal government asking for data on how many tests were distributed. I filed it through MuckRock’s portal, so both the original request and my correspondence with the U.S. Postal Service’s records office are publicly available.

Last week, the USPS fulfilled my request. While I’d requested data by state, county, and/or ZIP code, the agency only sent over at-home test orders and distribution numbers by state. According to the formal response letter they sent, more granular data would (somehow) count as “commercial information” and is therefore exempt from FOIA.

Now, obviously, I think that far more data on the test distribution program should be publicly available. As I wrote back in January when the program started, in order to truly evaluate the success of this program, we need test distribution numbers by more specific geographies and demographic groups.

Still, the state-by-state data are better than nothing. With these data, we can see that states with the highest volume of at-home test orders fall on the East and West coasts, with people living in the South and Midwest less likely to use the program.

(The population data that I used to calculate these per capita rates are from the HHS Community Profile Report.)

With the data from my FOIA request, we can see that states with higher vaccination rates also had more people taking advantage of the free COVID-19 test program. States like Vermont and Hawaii rank high up for both metrics, while states like North Dakota and Wyoming are on the lower end for both.

At the same time, many of the states where fewer people ordered the free tests are also states that saw higher COVID-19 death rates in 2022. In Mississippi, for example, about 433 people died of COVID-19 for every 100,000 residents since the year started—the highest death rate of any state. But people in the state ordered free tests at a rate under 0.3 per capita.

These charts basically confirm what many public health experts suspected about the free COVID-19 test program: Americans who already were more protected against COVID-19 (thanks to vaccination) were most likely to order tests. Just as we’re seeing now with the Omicron-specific booster shots, a valuable public health measure went under-utilized here.

I invite other journalists to report on these data; if you do, please link back to my original FOIA request on MuckRock!

More testing data

-

The CDC’s isolation guidance is not based on data

A study published in the CDC’s own journal indicated that about half of people infected with Omicron are still contagious 5-10 days after their isolation period starts. Chart via CDC MMWR. Maybe it’s because I’m a twenty-something living in the Northeast, but: quite a few of my friends have gotten COVID-19 in the last couple of weeks. The number of messages and social media posts I’m seeing about positive rapid tests isn’t at the level it was during the Omicron surge, but it’s notable enough to inspire today’s review of the CDC’s isolation guidance.

Remember how, in December, the CDC changed its recommendations for people who’d tested positive for COVID-19 to isolating for only five days instead of ten? And a bunch of experts were like, “Wait a second, I’m not sure if that’s sound science?” Well, studies since this guidance was changed have shown that, actually, a lot of people with COVID-19 are still contagious after five days. Yet the CDC has not revised its guidance at all.

(Also, to make sure we’re clear on the terms: isolation means avoiding all other human beings because you know that you have a contagious disease and don’t want to infect others. Quarantine means avoiding other humans because you might have the disease, due to close contact with someone who does or another reason for suspicion.)

The current CDC guidance still says that, if you test positive: “Stay home for 5 days and isolate from others in your home.” Yet, in recent weeks, I’ve had a couple of friends ask me: “Hey, so it’s been five days, but… I’m not sure I’m ready to rejoin society. Should I take a rapid test or something?”

Yes. The answer is yes. Let’s unpack this.

Studies indicating contagiousness after five days

As this NPR article on isolating with Omicron points out, the CDC guidance was “largely based on data from prior variants.” At the time of this five-day recommendation, in late December, scientists were still learning about how Omicron compared to Delta, Alpha, and so on, particularly examining the mechanisms for its faster spread and lower severity.

But now, almost four months later, we know more about Omicron. This version of the coronavirus, research suggests, is more capable of multiplying in the upper respiratory tract than other variants. People infected with Omicron are able to spread the virus within a shorter time compared to past strains, and they are able to spread it for a higher number of days—even if their symptoms are mild.

One study that demonstrates this pattern is a preprint describing Omicron infections among National Basketball Association (NBA) players, compared to cases earlier in 2021. Researchers at Harvard’s and Yale’s public health schools, along with other collaborators, compared 97 Omicron cases to 107 Delta cases. NBA players are a great study subject for this type of research, because their association mandates frequent testing (including multiple tests over the course of a player’s infection).

The big finding: five days after their Omicron infections started, about half of the basketball players were still testing positive with a PCR test—and showing significant viral load, indicating contagiousness. 25% were still contagious on day six, and 13% were still contagious on day seven. These patients also saw less of a consistent pattern in the time it took to reach their peak contagiousness than the players infected with Delta.

From the NPR article:

“For some people with omicron, it happens very, very fast. They turn positive and then they hit their peak very quickly. For others, it takes many days” – up to eight or even 10 days after turning positive, says the study’s senior author, Dr. Yonatan Grad, an associate professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

While this NBA study is a preprint, other research has backed up its findings. One study from Japan, shared as a “preliminary report” in January, found that people infected with Omicron had the highest levels of viral RNA—indicating their highest levels of contagiousness—between three and six days after their symptoms started. The researchers saw a “marked decrease” in viral RNA only after ten days.

Another preprint, from researchers at the University of Chicago (and antigen test proponent Michael Mina), examined Omicron infections among healthcare workers at the university medical center. Out of 309 rapid antigen tests performed on 260 healthcare workers, 134 (or about 43%) were positive results received five to ten days after these workers started experiencing symptoms.

The highest test positivity rate for these workers, according to the study, was “among HCW returning for their first test on day 6 (58%).” In other words, more than half of the workers were still infectious six days after their infection began, even though the CDC guidance would’ve allowed them to return to work.

Later in February, a study in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR)—or, the CDC’s own journal—shared similar results. The report, authored by CDC researchers and practitioners at a healthcare system in rural Alaska, looked at antigen test results from hundreds of infections reported to this health system during the Omicron wave.

The main finding: between five and nine days after patients were diagnosed with COVID-19, 54% (396 out of 729 patients) tested positive on rapid antigen tests. “Antigen tests might be a useful tool to guide recommendations for isolation after SARS-CoV-2 infection,” the authors wrote.

Following this, an early March preprint from researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital, MIT, Harvard, and other collaborators analyzed infections among 56 people during the Delta and Omicron waves. This study used viral cultures to examine contagiousness directly, rather than simply looking at test results.

Like past research, this study found that over half of patients (with both Omicron and Delta) were still contagious five days into their infections. About one-fourth were still contagious at day eight.

Guidance for people testing positive

All of the above studies suggest similar conclusions: about half of people infected with Omicron will still be contagious five days after their positive test results or the start of their symptoms, despite what the CDC’s guidance says. If you get infected with BA.2 in the coming surge, the best way to figure out whether you’re contagious after day five is by taking a rapid antigen test.

In fact, for the highest accuracy (and peace of mind), I’d recommend taking two antigen tests, two days in a row. If both are negative, then you’re probably good to return to society—but maybe don’t travel to visit an elderly relative just yet.

This two-rapid-test guidance comes from the U.K. Health Security Agency, which recommended in December that Brits could isolate for seven days instead of ten if they tested negative on days six and seven of their isolation. (The U.K.’s guidance has since become more lenient, but this is still a good rule for reference—more based in science than the CDC’s guidance.)

What else should you do if you test positive? Here are a few recommendations that I’ve been giving friends and family:

- Be prepared to isolate for a week or two, even if you may be able to leave isolation after a shorter period (with rapid tests).

- After leaving isolation, wear a good mask (i.e. an N95 or KN95) in all public spaces.

- Look into treatment options near you. The HHS has a database of publicly available COVID-19 therapeutics, while some localities (like New York City) have set up free delivery systems for these drugs.

- There’s also the HHS Test to Treat program, which allows people to get tested for COVID-19 and receive treatment in one pharmacy visit. This program has faced a pretty uneven rollout so far, though.

- Rest as much as possible, even if you have mild symptoms; patient advocates and researchers say that this reduces risk for developing Long COVID.

More testing data

-

Sources and updates, April 10

- Lessons learned from the non-superspreader Anime NYC convention: Last fall, one of the first Omicron cases detected in the U.S. was linked to the Anime NYC convention, a gathering of more than 50,000 fans. Many worried that the event had been a superspreader for this highly contagious variant, but an investigation from the CDC later found that, in fact, Omicron spread at the convention was minimal. My latest feature story for Science News unpacks what we can learn from this event about preventing infectious disease spread—not just COVID-19—at future large events. I am a big anime fan (and have actually attended previous iterations of Anime NYC!), so this was a very fun story for me; I hope you give it a read!

- States keep reducing their data reporting frequency: Last Sunday, I noted that Florida—one of the first states to shift from daily to weekly COVID-19 data updates—has now gone down to updating its data every other week. This is part of an increasing trend, writes Beth Blauer from the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 data team in a recent blog post. “As of March 30, only eight states and territories (AR, DE, MD, NJ, NY, PA, PR, and TX) report case data every day of the week,” Blauer says. And it seems unlikely that states will increase reporting frequencies again without a major change in public health funding or the state of the pandemic.

- Biden administration announces Long COVID task force: This week, the Biden administration issued a memo addressing the millions of Americans living with Long COVID. The administration is creating a new, interagency task force, with the goal of developing a “national research action plan” on Long COVID, as well as a report laying out services and resources that can be directed to people experiencing this condition. It’s worth noting that recent estimates from the U.K. indicate 1.7 million people in that country (or one in every 37 residents) are living with Long COVID; current numbers in the U.S. are unknown due to data gaps, but are likely on a similar scale, if not higher.

- New scientific data sharing site from the NIH: Not directly COVID-related, but an exciting new source: the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has created an online data repository for projects funded by and affiliated with the agency. The site currently includes over 100 datasets, including scientific data, genomic data, and clinical data; it also includes information on data management and sharing for researchers working on these projects. This press release from NIH has more info. (H/t Liz Essley Whyte.)

- Study indicates continued utility for COVID-19 testing in schools: During the Omicron surge, testing programs in a lot of schools collapsed, simply because institutions didn’t have enough resources to handle all of the students and staff getting sick. The surge led some schools to consider whether school testing programs are worth continuing at all. But a new study, released last week in The Lancet, suggests that yes, surveillance testing can still reduce transmission—even when schools are dealing with highly contagious variants. (Note that this was a modeling study, not a real-world trial.)

- Preprint shows interest in self-reporting antigen test results: Another interesting study released recently: researchers at the University of Massachusetts distributed three million free rapid, at-home antigen tests between April and October 2021, then studied how test recipients interacted with a digital app for ordering tests and logging results. About 8% of test recipients used the app, the researchers found; but more than 75% of those who used it did report their antigen test results to their state health agency. The results (which haven’t yet been peer-reviewed) suggest that, if institutions make it easy and accessible for people to self-report their test results, the reporting will happen.

-

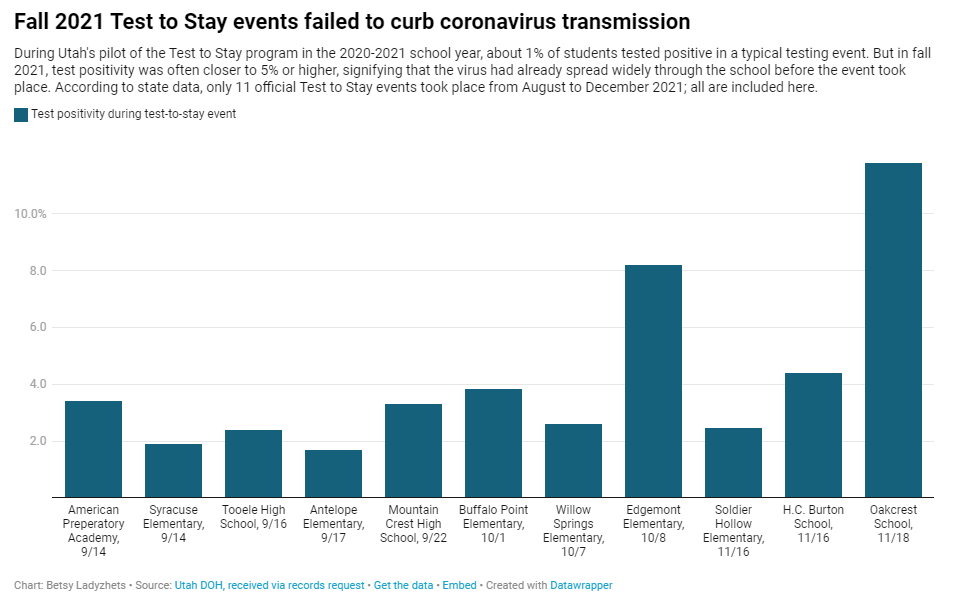

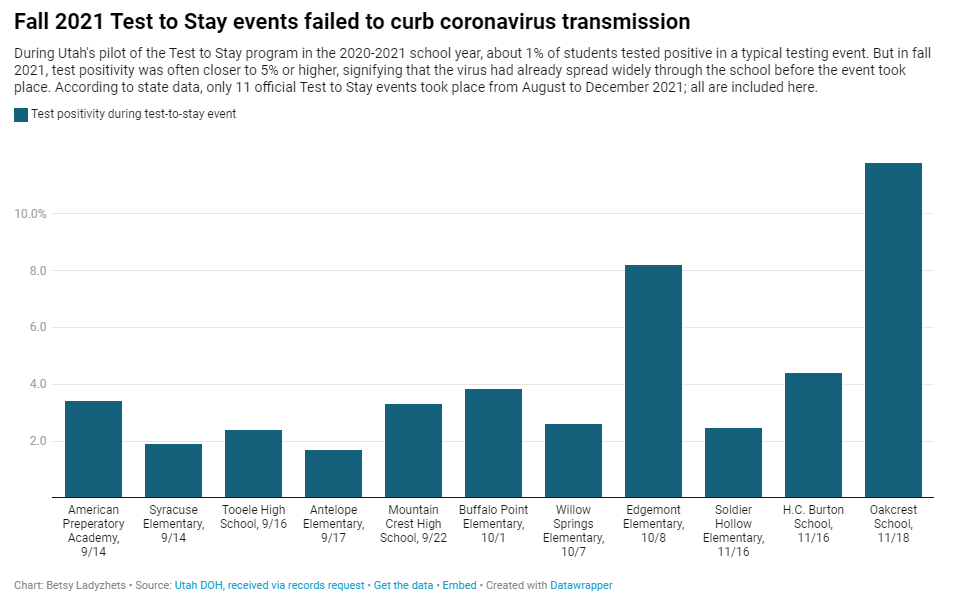

Why Utah’s innovative school COVID-19 testing program failed

In fall 2021, testing events at Utah public schools failed to decrease coronavirus transmission. My latest story with the Documenting COVID-19 project is an investigation into Utah’s school COVID-19 testing program, in collaboration with the Salt Lake Tribune.

As longtime readers know, I have done a lot of reporting on school COVID-19 testing programs. I find these efforts to routinely test K-12 students fascinating, in part because of the unique potential for collaboration between school districts, health departments, and other community institutions—and also because of the immense challenges that arise when schools are asked to become health providers in a way we never would’ve considered before the pandemic.

Utah’s program caught my eye last year when I was reporting a story for Science News on the hurdles schools faced in setting up COVID-19 testing. This state was an early pioneer of Test to Stay, a strategy in which students must test negative to attend school after a potential exposure rather than going through a (potentially unnecessary) quarantine.

In Utah’s version of Test to Stay, once 1% of students tested positive for the virus, the entire school would go through a testing event. Students who tested negative could keep attending school without interruption, while those who tested positive (or those who refused to participate) could quarantine. The Utah health department tested out this program in the 2020-2021 school year, and it was so successful that a CDC MMWR boasted it had “saved over 100,000 days of in-person instruction.”

After that successful test, Utah’s state legislature codified the program into law for the 2021-2022 school year. But Test to Stay crashed and burned this past fall, even before the Omicron variant overwhelmed Utah’s test supplies.

Here’s why the program failed, according to our investigation:

- When putting Test to Stay into law, the Utah state legislature doubled the threshold for school cases that would trigger a testing event, from 1% to 2% of the student body. (Or from 15 to 30 students at smaller schools with under 1,500 students.) This higher threshold allowed COVID-19 to spread more widely before testing events took place, leading to higher case numbers when students were finally tested.

- Utah’s lawmakers also banned schools from requiring masks in fall 2021, leading to more transmission. Experts said the original program was intended to be paired with masks and other safety measures; it was not able to stand on its own.

- In the 2020-2021 school year, Test to Stay was paired with a second program called Test to Play: mandatory testing every two weeks for students on sports teams and in other extracurriculars. Without this regular testing in fall 2021, Utah schools had less capacity to identify school cases outside of voluntary and symptomatic tests—so it took longer for schools to reach the Test to Stay threshold.

- The Utah health department allowed individual schools and districts to request rapid tests for additional surveillance testing. Some administrators requested thousands of tests and made them regularly available to students and staff; others were entirely uninterested and did not encourage testing at their schools.

- Testing in schools has become increasingly polarized in recent months, like all other COVID-19 safety measures. One school administrator told me that he faced some vocal parents who felt “that their rights were being trampled on” by the testing program. Without high numbers of students opting in to get tested, testing programs are inherently less successful.

Even though the CDC endorsed Test to Stay as part of its official school COVID-19 guidance last December—citing Utah’s program as a key example—its future in the state is now uncertain. State lawmakers paused the program during the Omicron surge in January and have yet to revive it. At the same time, lawmakers have made it even harder for Utah schools to make their own decisions around safety measures.

What school districts and health departments should actually be doing, experts told me, is stock up on rapid tests now so that they’re ready to do mass testing in future surges. It’s unlikely that the Omicron wave will be our last, much as some Utah Republicans might want to pretend that’s the case.

You can read my full story at MuckRock’s site here (in a slightly longer version) or at the Salt Lake Tribune here (in a slightly shorter version). And the documents underlying this investigation are available on the Documenting COVID-19 site here.

More K-12 reporting

-

Three more things, January 30

A couple of additional news items for this week:

- Two House Democrats called on the CDC to release more Long COVID data. This week, Rep. Ayanna Pressley (from Massachusetts) and Rep. Don Beyer (from Virginia) sent the CDC a letter insisting that the agency report estimates of Long COVID infection numbers, including demographic breakdowns by race, gender, and age. “Collecting and publishing robust, disaggregated demographic data will help us better understand this illness and ensure that we are targeting lifesaving resources to those who need them most,” said Rep. Pressley in a statement to the Washington Post. While studies that may, theoretically, help provide such data are in the works via the National Institutes of Health’s RECOVER consortium, the consortium has yet to release any results. Long COVID continues to represent one of the biggest COVID-19 data gaps in the U.S.

- We don’t know yet whether cannabis can treat COVID-19, despite promising early studies. Recent studies have shown that CBD, along with other products containing marijuana and hemp, has some capacity to block coronavirus spread in the body in lab-grown cells and in mice. The studies were quickly turned into sensationalist headlines, even though it’s too early to say whether these products could actually be used to treat COVID-19. An excellent STAT News article by Nicholas Florko and Andrew Joseph describes the studies and their limitations, as well as how these early reports of COVID-19 treatment potential are “adding to the FDA’s existing CBD headache” when it comes to regulating these products.

- Have you received your free at-home rapid tests from the USPS yet? Last week, I described the federal government’s effort to distribute at-home rapid tests to Americans free of charge, along with the equity issues that have come with this initiative so far. This week, I saw some reports on social media indicating that people have started receiving their tests! Have you gotten your tests yet? If you have, I would love to hear from you—in absence of formal data from the USPS, maybe we can do some informal data collection on test shipping times within the COVID-19 Data Dispatch community.

Note: this title and format are inspired by Rob Meyer’s Weekly Planet newsletter.

-

CovidTests.gov early rollout raises equity concerns; where’s the data?

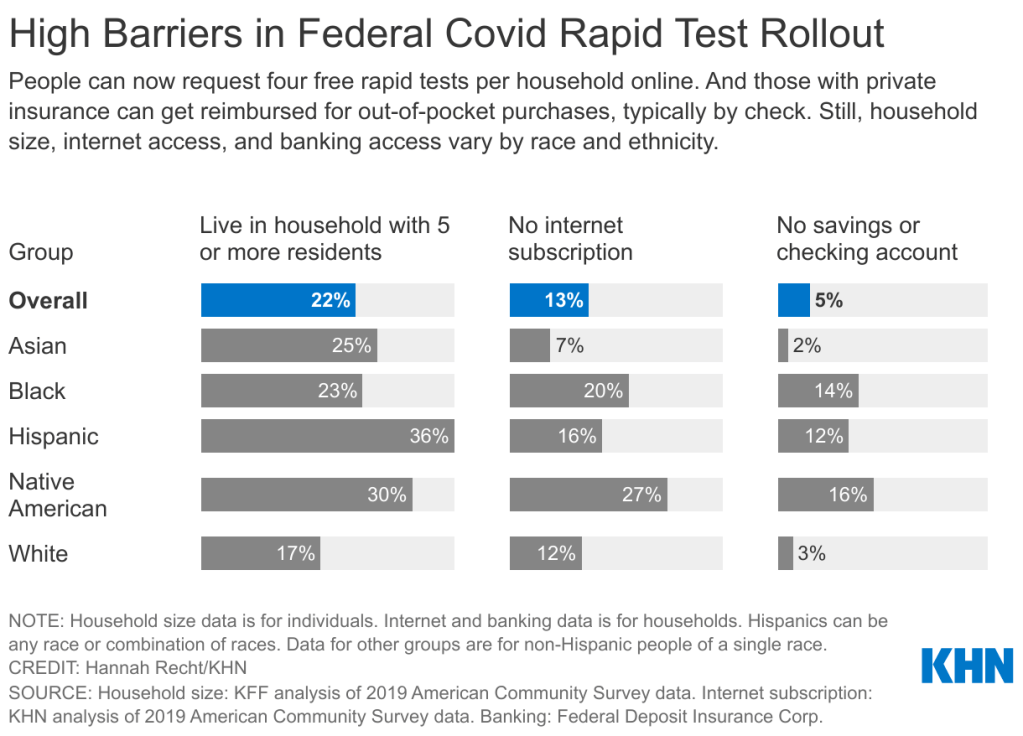

The federal government’s policies aimed at helping Americans get free rapid tests are insufficient for many households including people of color. Graphic via KHN. This week, the U.S. government unveiled a new website where Americans can get free at-home COVID-19 tests. The site is hosted by the U.S. Postal Service (USPS)—which will also distribute the tests—and it’s been lauded for its straightforward navigation and ability to handle a high level of traffic, both of which are unusual with government sites.

On Tuesday, the site went live early in “beta test” form before its formal launch on Wednesday. Within hours of it going live, public health experts were already raising equity concerns about the free test distribution program. To address these concerns, the federal government should release data on where the free tests go—including breakdowns by state, county, ZIP code, race and ethnicity, the tests’ delivery dates, and more.

As the link to the testing order site was shared widely on social media, one thing quickly became clear: people who lived in high-density settings were at a disadvantage. Americans in traditional apartment buildings, houses split into multiple living spaces, dormitories, and other multi-unit dwellings attempted to order tests—only to get an error message stating someone at their address had ordered tests already.

The USPS ordering page is set up to allow just one test order per address, to prevent people from abusing the free test program. But, despite having literally every address in the U.S. on file, the USPS apparently failed to account for many apartment buildings. Some apartment-dwellers were able to get around this issue by placing their apartment number on the first address line, removing “Apt” from the address, or otherwise adjusting how they filled out the form, but these tricks didn’t work for everyone.

I myself ordered the free tests before I learned about these issues on Twitter; I later sheepishly texted the groupchat for my Brooklyn, seven-unit apartment building, preemptively apologizing in case I’d fucked up my neighbors’ chances of obtaining free tests. (Luckily, my building seemed to be unaffected by the USPS issue—one of my neighbors responded saying that she was able to order the tests without a problem.)

This issue “stems from buildings not being registered as multi-unit complexes and affected only a ‘small percentage of orders,’” the USPS said in a statement to POLITICO. And people facing this issue as they order tests can file a service request with USPS or call the agency at 1-800-ASK-USPS, according to KHN.

Still, a “small percentage of orders” could add up to millions of people living in multi-unit housing who were unable to obtain free tests, or would have to share just four tests among an apartment building’s worth of residents. Without more precise data, it’s hard to understand the scope of this problem.

All the Twitter discourse about apartment buildings obscures another group that shouldn’t have to share a small number of tests among many people: large households. The USPS is sending just four tests in each order—not four testing kits, four individual tests. That’s not enough for a family of four to test themselves according to FDA recommendations (i.e. twice within two days) after a potential exposure; it’s certainly not enough for large families including five or more people.

And minority communities are more likely to include such large households. According to a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of Census data: “More than a third of Hispanic Americans plus about a quarter of Asian and Black Americans live in households with at least five residents…Only 17% of white Americans live in these larger groups.”

Households in West coast states are also more likely to include five or more residents, according to a similar analysis from the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill’s Carolina Demography center. States with the highest shares of five or more resident households are: Utah (18.8%), California (13.7%), Hawaii (13.5%), Idaho (13.2%), and Alaska (12.9%). On the other hand, in some East coast states, under 7% of households include five or more residents.

!function(){“use strict”;window.addEventListener(“message”,(function(e){if(void 0!==e.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var t=document.querySelectorAll(“iframe”);for(var a in e.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var r=0;r<t.length;r++){if(t[r].contentWindow===e.source)t[r].style.height=e.data["datawrapper-height"][a]+"px"}}}))}();The USPS test distribution system also gave an advantage to Americans with internet access. At one point on Tuesday afternoon, the USPS order site was drawing more than half of all government website traffic, demonstrating its popularity with internet users—while people without internet were not yet able to order tests.

As of Friday, those without internet access can order the free tests over the phone, at 1-800-232-0233. This phone line is open daily from 8 AM to midnight Eastern Time, according to NPR, and Americans can order in over 150 languages. The USPS website itself is available in English, Spanish, and Chinese.

While this phone line is very helpful now, the delay between the website’s release (on Tuesday) and the phone line’s release (on Friday) means that Americans without internet may be behind in the queue for actually receiving their tests. Already, the federal government has said that people who ordered their tests may need to wait for weeks to receive their tests.

Of course, as analysis from KHN has shown, Americans of color are less likely to have internet access than their white neighbors. 27% of Native Americans, 20% of Black Americans, and 16% of Hispanic Americans have no internet subscription, compared to 12% of white Americans.

Finally, the USPS test distribution system leaves out one major group of vulnerable Americans: those who don’t have an address at all. Homeless people are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19: many outbreaks have occurred in shelters, and many of these people have health conditions that increase their risk of severe symptoms. The impact of COVID-19 among homeless Americans is not well understood due to a lack of data collection; still, we know enough to indicate free tests should be a priority for this group.

The White House has said that equity will be a priority for the free rapid test rollout: each day, 20% of test shipments will go to people who live in highly vulnerable communities, as determined by the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index. This index ranks ZIP codes according to the communities’ ability to recover from adverse health events, based on a number of social, environmental, and economic factors.

This priority is nice to hear. But without data on the test rollout, it’ll be difficult to evaluate how well the federal government is living up to its promise of equitable test distribution. I’d like to see data on the free test distribution that goes to the same level of detail as the data on our vaccine distribution, if not even more granular.

The data could include: tests distributed by state, county, and ZIP code; tests distributed to ZIP codes that rank highly on the Social Vulnerability Index; tests distributed by race, ethnicity, age, gender, and household size; dates that tests were ordered and delivered; tests delivered to single- and multi-unit buildings; and more.

Unlike other COVID-19 metrics that are difficult to collect and report at the federal level, the federal government literally has all of this information already—they’re collecting the address of every person that orders tests! There is no excuse for the government not to make these data public.

In short: USPS, where is your free rapid test distribution dashboard? I’m waiting.

More posts on testing

-

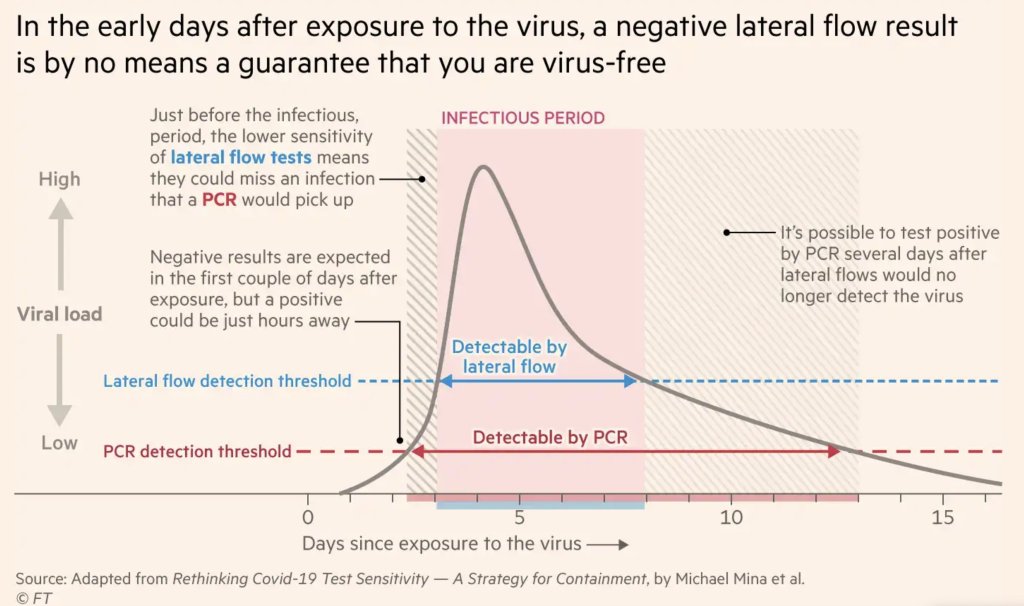

FAQ: Testing and isolation in the time of Omicron

After exposure to the coronavirus, someone may test negative on rapid antigen tests for multiple days before their viral load becomes high enough for such a test to detect their infection. Chart by Michael Mina, adapted by the Financial Times. As Omicron spreads rapidly through the U.S., this variant is driving record case numbers—and record demand for testing, including both PCR and rapid at-home tests. In other words, it feels harder than ever to get tested for COVID-19, largely because more people currently need a test due to recent exposure to the virus than at any other time during the pandemic.

Also this week, the CDC changed its guidance for people infected with the coronavirus: rather than isolating for 10 days after a positive test, Americans are now advised to isolate for only five days, if they are asymptomatic. Then, for the following five days, people should wear a mask in all public settings. This guidance change has prompted further discussion (and general confusion) about who needs to get tested for COVID-19, when, and how.

Here’s a brief FAQ, to help navigate this complicated testing-and-isolation landscape. In addition to the CDC guidance, it’s inspired by a recent question from a reader about testing and isolation following a positive PCR result in her family.

What’s the difference between being infected and being contagious?

As we think about interpreting COVID-19 test results in the Omicron era, it’s key to distinguish between being infected with the coronavirus and being actively contagious.

- Infected: The virus is present in your body.

- Contagious: The virus is present in your body at high enough levels that you can potentially spread it to other people.

In a typical coronavirus infection, it takes a couple of days after you encounter the virus—i.e. breathe the same air as someone who was contagious—for the coronavirus to build up enough presence in your body that tests can begin detecting it. PCR tests can typically detect the virus within one to three days after an infection begins, while rapid tests may take longer.

How do you use testing to tell if you’re infected and/or contagious?

Timing is extremely important with coronavirus tests, and has become even more so with Omicron. If you learn about a recent exposure to the virus, you don’t want to get tested immediately after that exposure, since the test would not pick up a potential infection yet. Say you had dinner with a friend on Wednesday, and they tell you on Thursday that they just tested positive; you should wait until Friday or Saturday to get tested with PCR, or until Saturday or Sunday to get tested with a rapid at-home test. (And ideally, you would avoid interacting with other people while you wait to get tested.)

PCR tests can detect the virus within a couple of days of infection. Rapid tests, which are less precise, generally can’t detect the virus until it’s at high enough levels for someone to be contagious. This can take time—though Omicron may have shortened the window between infection and becoming contagious to just three days, according to some early studies. A new CDC study released this week provides additional evidence here.

This chart, an adaptation of a figure by rapid test expert Michael Mina published in the Financial Times, shows how someone could potentially test negative on rapid tests for multiple days after a coronavirus exposure, even though they are infected:

When this person tests positive on a rapid test, the result indicates that they’ve become contagious with the virus. Then, it’s possible that the person may continue testing positive on PCR tests after they stop testing positive with antigen tests, because they are no longer contagious but continue to carry enough virus genetic material that a PCR test can pick it up.

How do you get ahold of rapid tests, in the first place?

In order to use rapid tests to tell whether you’re contagious with the coronavirus, you need to get some rapid tests! Here are a couple of suggestions:

- Order online from Walmart: If you look at this website right now, Walmart will probably say that Abbott BinaxNOW rapid tests are out of stock. But if you leave the page open and refresh often, you may be able to snag some rapid tests right after Walmart restocks (which happens roughly once a day, I think). I like ordering from Walmart because they’re cheaper than other BinaxNOW vendors and ship quickly, usually within a week.

- Order online from iHealth Labs: iHealth Labs is one rapid test manufacturer that’s grown in popularity recently, as an alternative to BinaxNOW. You can order up to 10 packs (with two tests each) directly from the manufacturer, and report test results in an app. In my experience, though, iHealth Labs is slower to ship than other distributors; an order I placed on December 22 is due to arrive two weeks later, on January 5.

- Use NowInStock to see availability: This website tracks rapid test availability at a number of websites, including CVS, Walgreens, Walmart, Amazon, and others. It’s helpful to see your options for a number of different tests, but bear in mind that tests sold by third-party vendors (like Amazon) may be less reliable than those sold directly by pharmacies.

- Follow local news: A lot of city and state governments have recently started making rapid tests available to the public for free, from D.C. libraries to Connecticut towns. I recommend keeping an eye on local news and government websites in your area to look for similar initiatives—or, if your area isn’t making rapid tests available, call your local representative and ask that they do!

Why did the CDC change its guidance for isolation?

As I mentioned above, the CDC recently changed its guidance for people who test positive for the coronavirus. If someone has no symptoms five days after their positive test result, they can stop isolating from others—but they need to wear a mask in all public settings.

According to the CDC, the new guidance is “motivated by science demonstrating that the majority of SARS-CoV-2 transmission occurs early in the course of illness, generally in the 1-2 days prior to onset of symptoms and the 2-3 days after.” In other words, the CDC is saying that people are generally contagious for a few days after their symptoms start. After that, they’re less likely to infect others, so isolation may be less necessary—and good mask-wearing may be sufficient to prevent further coronavirus spread.

Many experts are attributing the guidance chance to economic needs: as Omicron causes flight cancellations, closed restaurants, and other business disruptions, a shorter isolation period can help people get back to work more quickly. The recent isolation change follows a similar guidance change the previous week, which said healthcare workers could shorten their isolation periods if their facilities were experiencing staffing shortages.

What are experts saying about the new guidance?

Much of the commentary is not positive. While the CDC said the new guidance is “motivated by science,” the agency has failed to cite specific studies backing it up—though some such studies exist, as Dr. Katelyn Jetelina discusses in this Your Local Epidemiologist post.

Generally, it does seem that most people—particularly vaccinated people—are no longer contagious five days after their symptoms start. (Reminder: five days after symptoms start could be seven to nine days into the infection period, since it takes time for the virus to build up in your body and cause symptoms.) But this is by no means guaranteed for everyone, as each person infected with the coronavirus has a unique COVID-19 experience.

As a result, many experts have said that the CDC should have required negative rapid tests for people to leave isolation after five days. A negative rapid test would indicate that someone is no longer contagious, the argument goes, and they can then go back into the world. In the U.K., two negative rapid test results are required to shorten isolation from ten to seven days.

However, for everyone in the U.S. to be able to rapid test out of isolation, the country would need a far greater supply of those tests than we currently have available. This Twitter thread, by epidemiologist Matt Ferrari, explains the challenges posed by limited rapid testing:

Ferrari argues that the CDC guidance makes sense, given the information and resources currently available in the U.S., as well as the fact that simpler rules are easier to follow. Still, I personally would say that, if you have the rapid tests available to test out of isolation, you should.

More Omicron reporting