In the past week (October 20 through 26), the U.S. reported about 270,000 new COVID-19 cases, according to the CDC. This amounts to:

- An average of 38,000 new cases each day

- 81 total new cases for every 100,000 Americans

- 2% more new cases than last week (October 13-19)

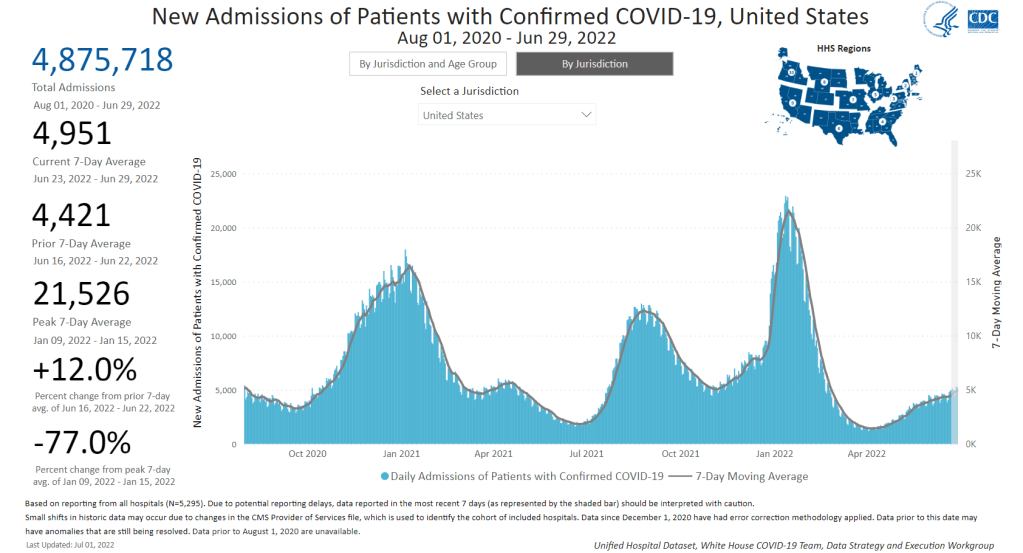

In the past week, the U.S. also reported about 23,000 new COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals. This amounts to:

- An average of 3,200 new admissions each day

- 6.9 total admissions for every 100,000 Americans

- 1% more new admissions than last week

Additionally, the U.S. reported:

- 2,600 new COVID-19 deaths (380 per day)

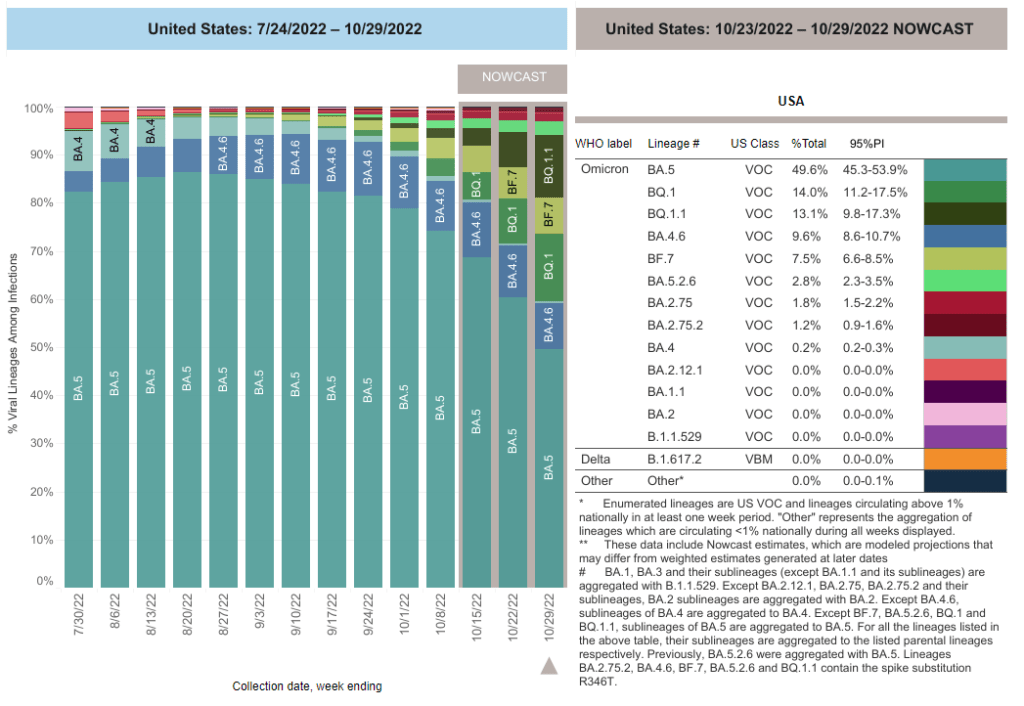

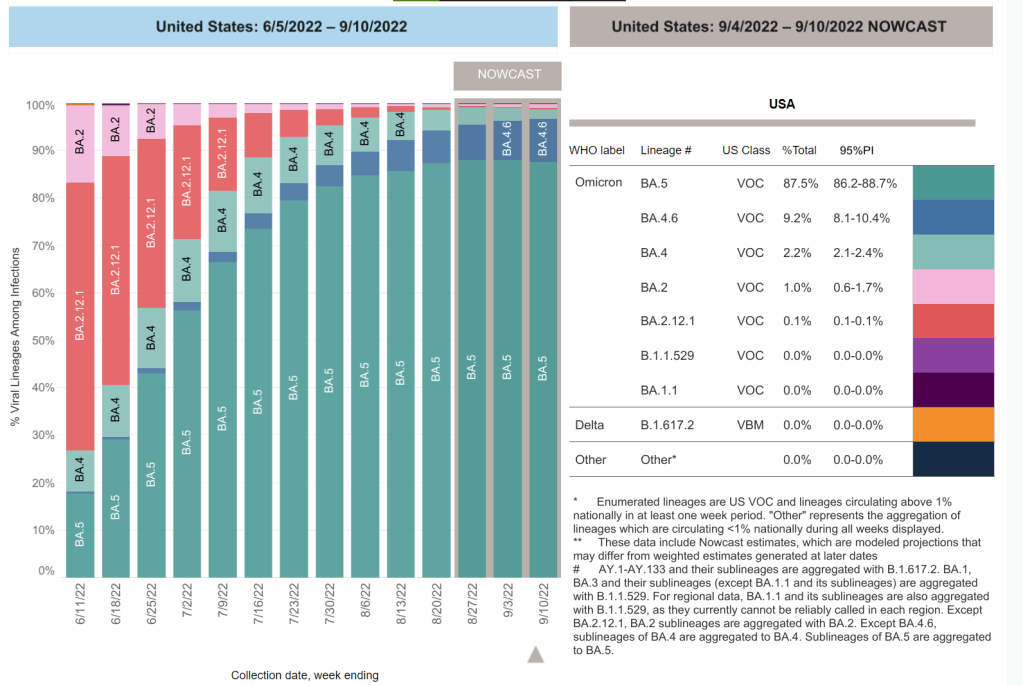

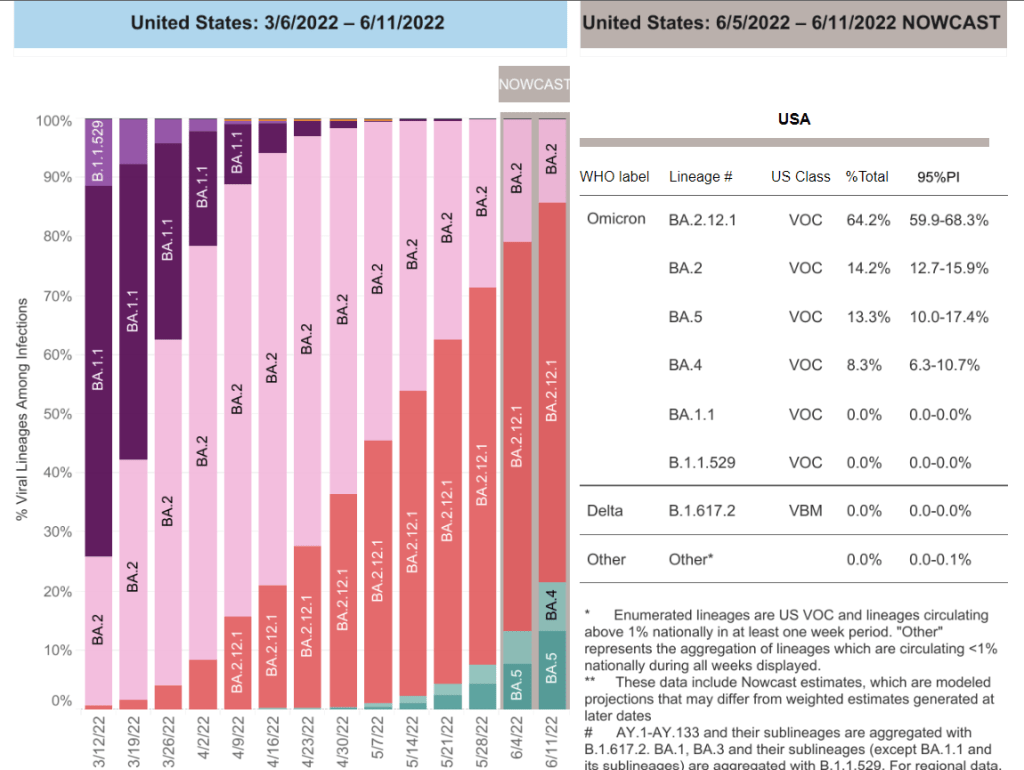

- 27% of new cases are caused by Omicron BQ.1 and BQ.1.1; 8% by BF.7; 3% by BA.2.75 and BA.2.75.2 (as of October 29)

- An average of 400,000 vaccinations per day

The national COVID-19 picture continues to be somewhat murky, thanks in part to poor-quality data. Both nationwide cases and new hospital admissions trended slightly upward in the last week (by 2% and 1%, respectively); this could reflect the beginnings of fall surges in some places, but it’s hard to say for sure.

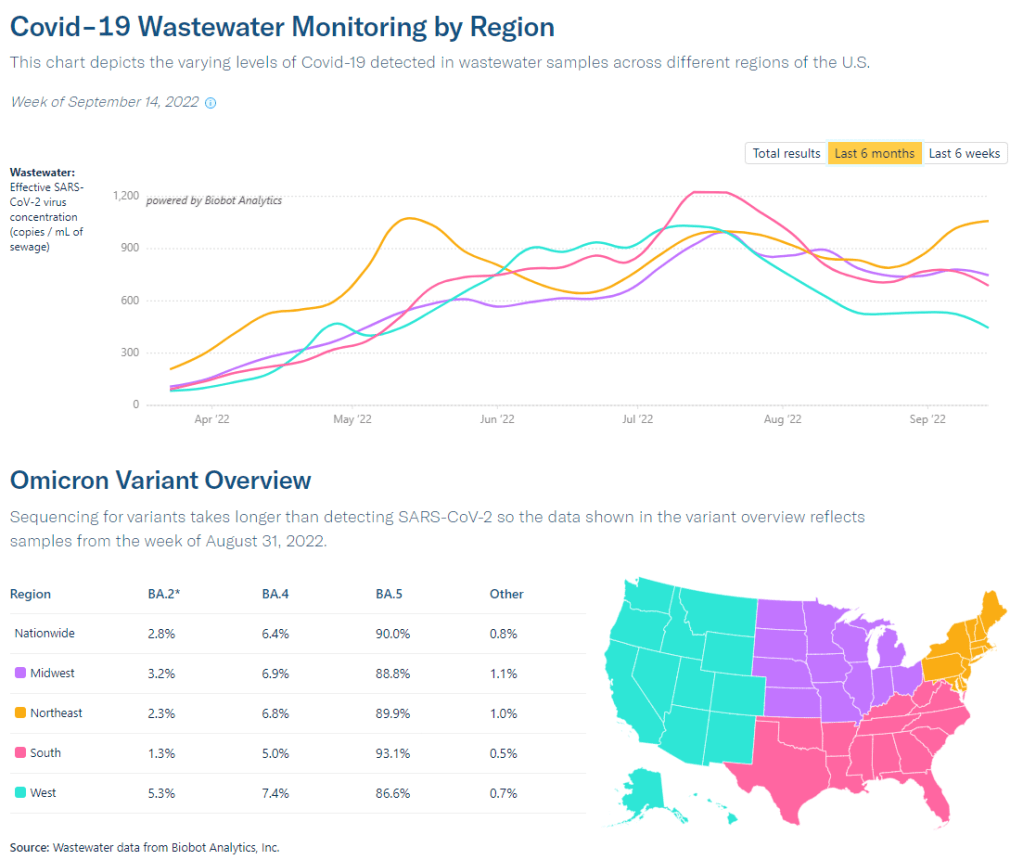

Wastewater data from Biobot continue to suggest the Northeast is seeing more COVID-19 transmission than other parts of the country, though this region reported a decrease in viral levels over the last two weeks. Other regions are reporting plateaus in transmission, according to Biobot.

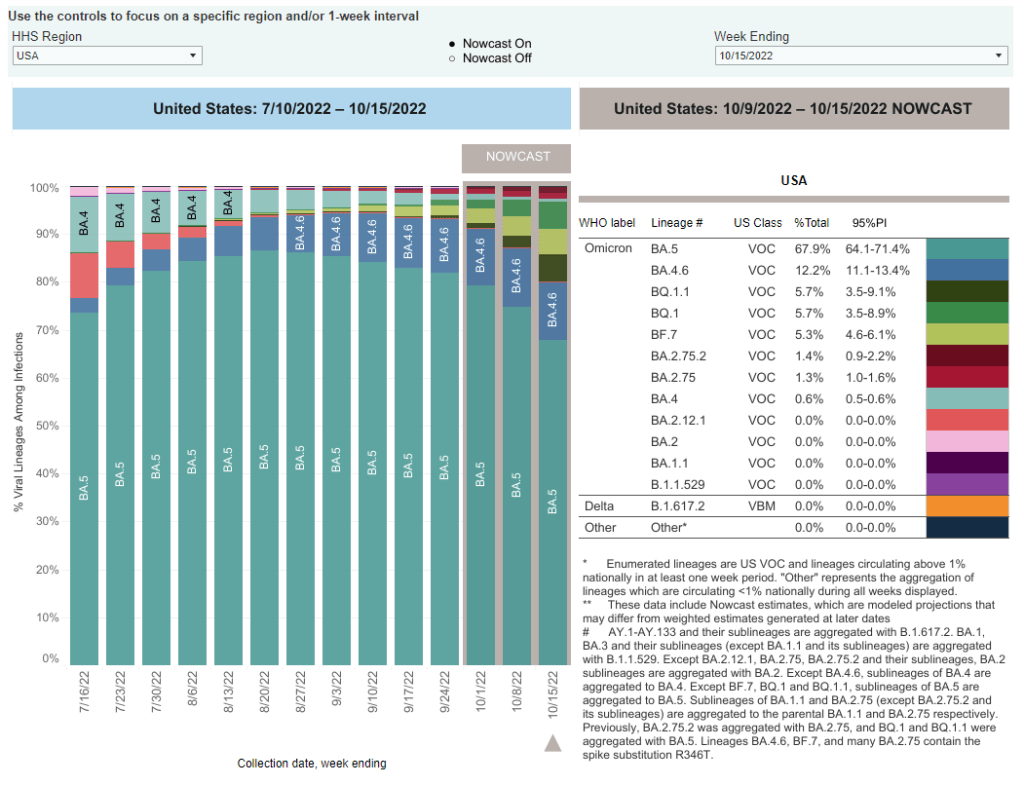

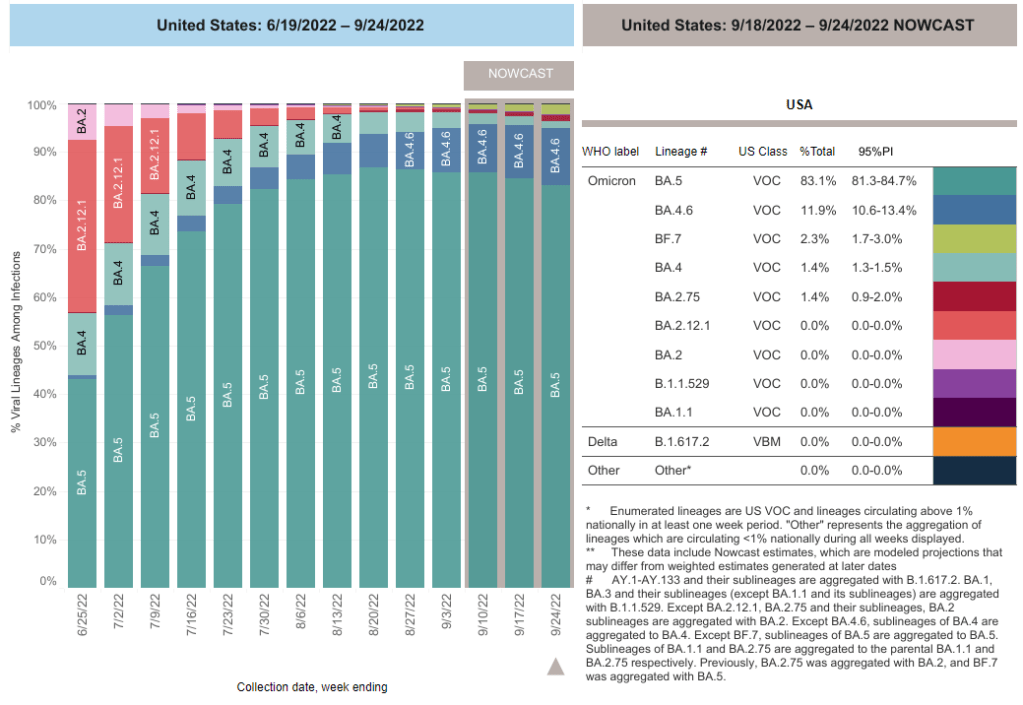

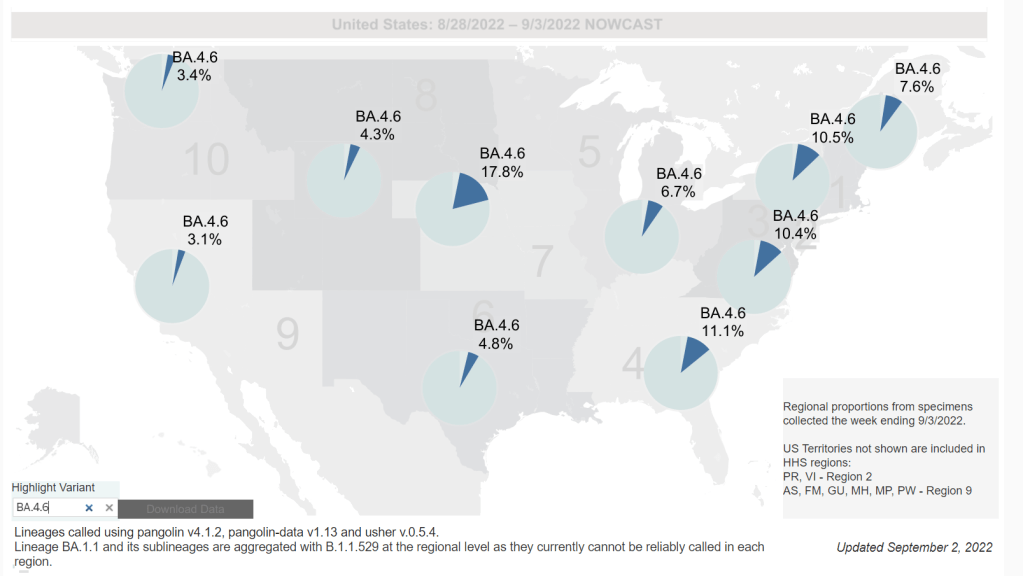

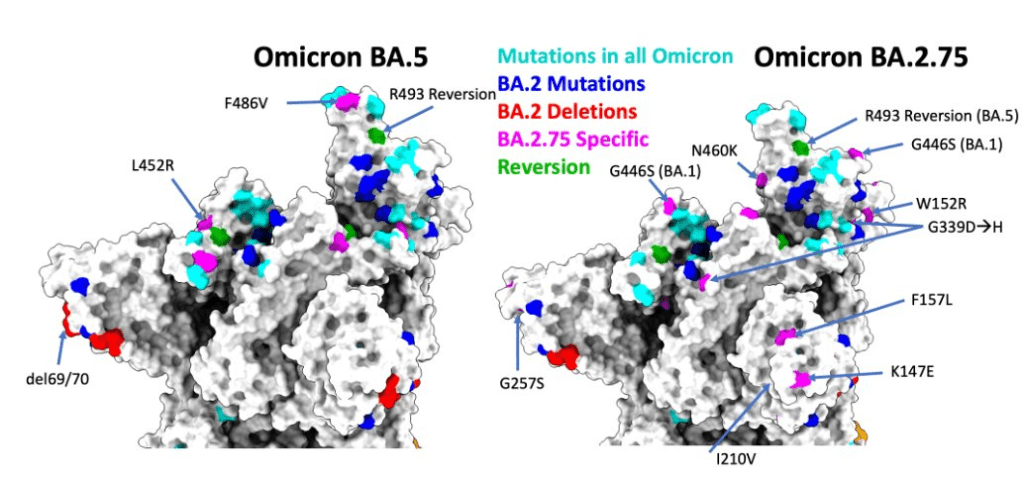

One reason we’re not seeing a definitive national surge yet could be that the newest iterations of Omicron have yet to fully dominate the country. BA.5 caused just under half of new COVID-19 cases nationwide last week, according to the CDC’s latest estimates, but the remaining half of cases were driven by a variety of new lineages: BQ.1, BQ.1.1, BA.4.6, and BF.7 all contributed over 5%.

When one of these subvariants (likely BQ.1.1) outcompetes the others, we will likely see a clearer picture of its impact on transmission. Also worth noting: XBB, the subvariant spreading quickly in Singapore and other Asian countries, has been identified in the U.S.—though its prevalence is too minimal to show up in the CDC’s estimates, at this point.

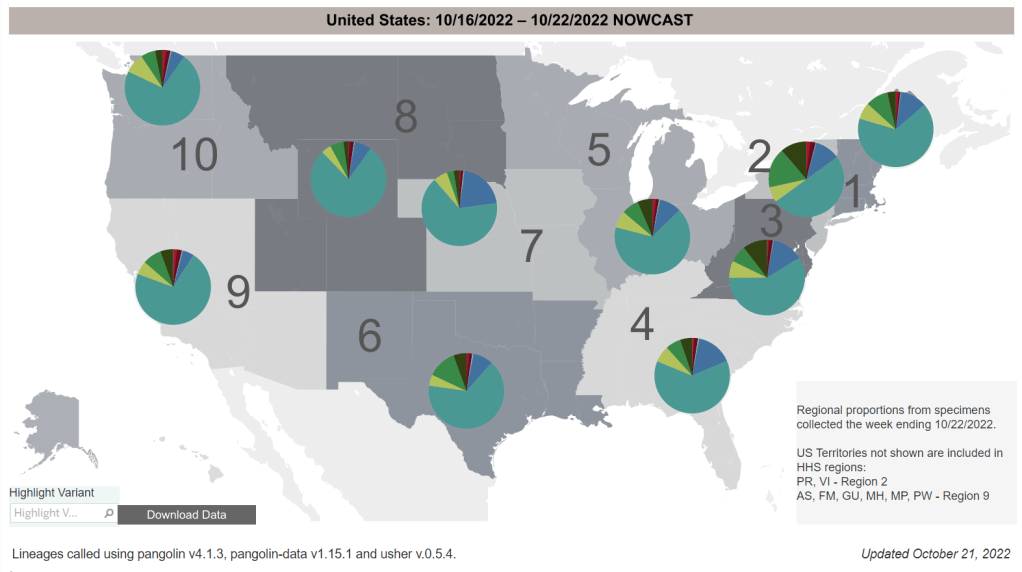

New York is a hotspot again: the state has a higher prevalence of BQ.1 and BQ.1.1 than other parts of the country, and some experts are concerned about rising COVID-19 hospitalizations here. In New York City, official cases have remained relatively stable for the last few weeks even as hospitalizations are going up, suggesting how continued low testing may make cases even less useful as a metric to watch.

This isn’t the only region seeing the start of a fall surge, though. The Twin Cities area in Minnesota reported a major spike in wastewater this week, with viral prevalence the highest it’s been since the original Omicron surge. Some counties in the South and West coast are showing similar warnings, according to Biobot’s dashboard.

And COVID-19 isn’t the only respiratory virus wreaking havoc right now, as we’ll discuss more in this issue. Places like NYC are seeing rising hospitalizations from the flu and RSV, placing additional strain on an already-overburdened healthcare system. Even if the coronavirus doesn’t have a drastic surge this winter, we could still see a lot of respiratory infections.