On Thanksgiving, my Twitter feed was dominated not by food photos, but by news of a novel coronavirus variant identified in South Africa earlier this week. While the variant—now called Omicron, or B.1.1.529—likely didn’t originate in South Africa, data from the country’s comprehensive surveillance system provided enough evidence to suggest that this variant could be more contagious than Delta, as well as potentially more able to evade human immune systems.

Note that the words suggest and could be are doing a lot of work here. There’s plenty we don’t know yet about this variant, and scientists are already working hard to understand it.

But the early evidence is substantial enough that the World Health Organization (WHO) designated Omicron as a Variant of Concern on Friday. And, that same day, the Biden administration announced new travel restrictions on South Africa and several neighboring countries. (More on that later.)

In today’s issue, I’ll explain what we know about the Omicron variant so far, as well as the many questions that scientists around the world are already investigating. Along the way, I’ll link to plenty of articles and Twitter threads where you can learn more. As always, if you have more questions: comment below, email me, (betsy@coviddatadispatch.com), or hit me up on Twitter.

Where did the Omicron variant come from?

This is one major unknown at the moment. South Africa was the first country to detect Omicron this past Monday, according to STAT News. But the variant likely didn’t originate in South Africa; rather, this country was more likely to pick up its worrying signal because it has a comprehensive variant surveillance system.

Per The Conversation, this system includes: “a central repository of public sector laboratory results at the National Health Laboratory Service, good linkages to private laboratories, the Provincial Health Data Centre of the Western Cape Province, and state-of-the-art modeling expertise.”

Researchers from South Africa and the other countries that have detected Omicron this week are already sharing genetic sequences on public platforms, driving much of the scientific discussion about this variant. So far, one interesting aspect of this variant is that, even though Delta has dominated the coronavirus landscape globally for months, Omicron did not evolve out of Delta.

Instead, it may have evolved over the course of a long infection in a single, immunocompromised individual. It also may have flown under the radar in a country or region with poor genomic surveillance—which, as computational biologist Trevor Bedford pointed out on Twitter, is “certainly not South Africa”—and then was detected once it landed in that country.

Why are scientists worried about Omicron?

Omicron seems to be spreading very quickly in South Africa—potentially faster than the Delta variant. Based on publicly available sequence data, Bedford estimated that it’s doubling exponentially every 4.8 days.

An important caveat here, however, is that South Africa had incredibly low case numbers before Omicron was detected—its lowest case numbers since spring 2020, in fact. So, we cannot currently say that Omicron is “outcompeting” Delta, since there wasn’t much Delta present for Omicron to compete with. The current rise in cases may be caused by Omicron, or it may be the product of a few superspreading events that happen to include Omicron; we need more data to say for sure.

Still, as Financial Times data reporter John Burn-Murdoch pointed out: “There’s a clear upward trend. This may be a blip, but this is how waves start.”

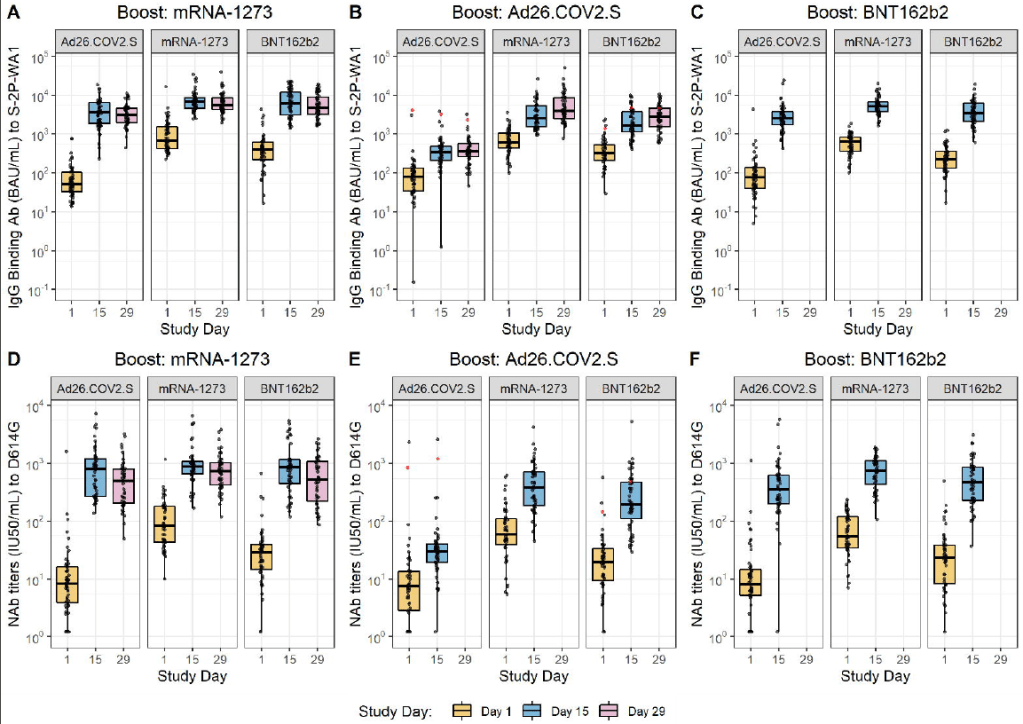

Another major cause for concern is that Omicron has over 30 mutations on its spike protein, an important piece of the coronavirus that our immune systems learn to recognize through vaccination. Some of these mutations may correlate to increased transmission—meaning, they help the virus spread more quickly—while other mutations may correlate to evading the immune system.

Notably, a lot of the mutations on Omicron are mutations that we simply haven’t seen yet in other variants. On this diagram from genomics expert Jeffrey Barrett, the purple, yellow, and blue mutations are all those we haven’t seen on previous variants of concern, while the red mutations (there are nine) have been seen in previous variants of concern and are known to be bad.

Some of these new mutations could be terrible news, or they could be harmless. We need more study to figure that out. This recent article in Science provides more information on why scientists are worried about Omicron’s mutations, as well as what they’re doing to investigate.

How many Omicron cases have been detected so far?

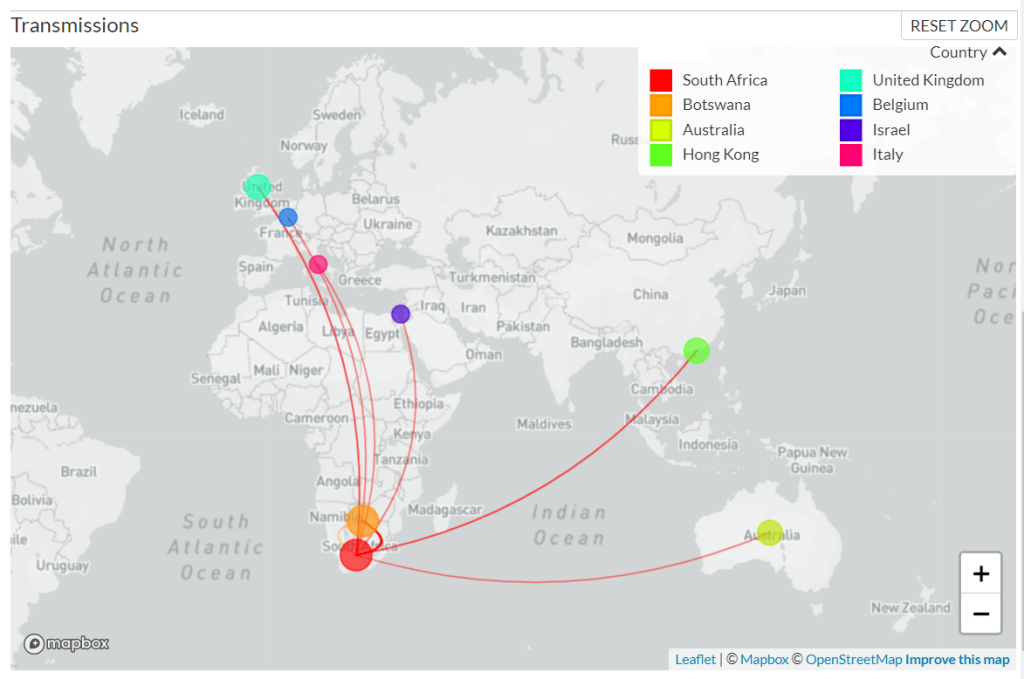

As of Sunday morning, genetic sequences from 127 confirmed Omicron cases have been shared to GISAID, the international genome sharing platform. The majority of these cases (99) were identified in South Africa, while 19 were identified in nearby Botswana, two in Hong Kong, two in Australia, two in the U.K., one in Israel, one in Belgium, and one in Italy.

According to BNO News, over 1,000 probable cases of the variant have already been identified in these countries. Cases have also been identified in the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, the Czech Republic, and Austria. Many of the cases in the Netherlands are connected to a single flight from South Africa; the travelers on this flight were all tested upon their arrival, and 61 tested positive—though authorities are still working to determine how many of those cases are Omicron.

The U.K. Health Security Agency announced on Saturday that it had confirmed two Omicron cases in the country. Both of these cases, like those in Israel and Belgium, have been linked to travel—though the Belgium case had no travel history in South Africa. “This means that the virus is already circulating in communities,” Dr. Katelyn Jetelina writes in a Your Local Epidemiologist post about Omicron.

Omicron hasn’t been detected in the U.S. yet. But the CDC is closely monitoring this variant, the agency announced in a rather sparse Friday press release.

Luckily, Omicron is easy to identify because one of its spike protein mutations enables detection on a PCR test—no genomic sequencing necessary. Alpha, the variant that originated in the U.K. last winter, has a similar quality.

How does Omicron compare to Delta?

This is another major unknown right now. As I mentioned earlier, Omicron is spreading quickly in South Africa, at a rate faster than Delta spread when it arrived in the country a few months ago. But South Africa was seeing a very low COVID-19 case rate before Omicron arrived, making it difficult to evaluate whether this new variant is directly outcompeting Delta—or whether something else is going on.

(Note that a couple of the tweets below refer to this variant as “Nu,” as they were posted prior to the WHO designating it Omicron.)

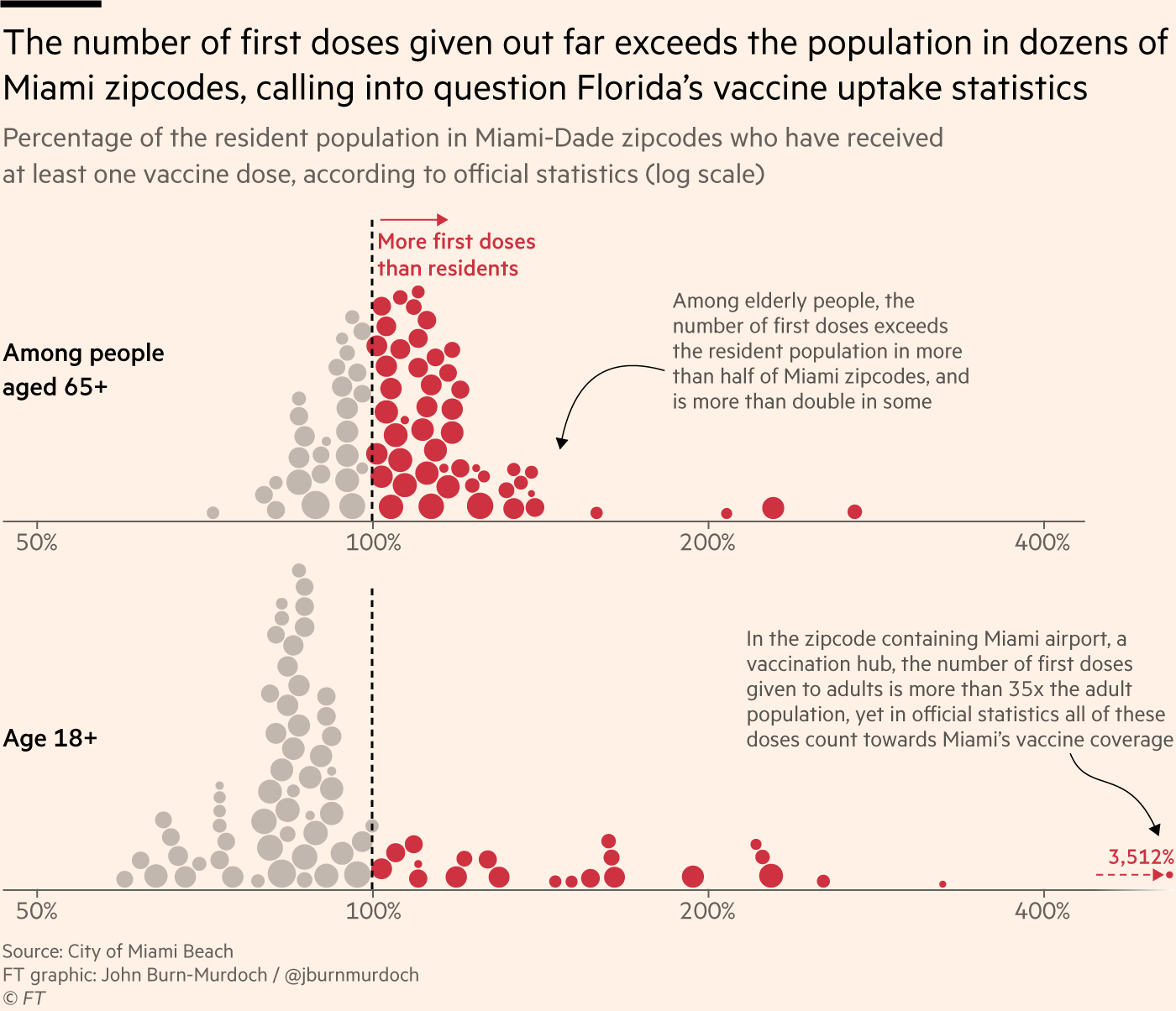

We also don’t know if Omicron could potentially evade the human immune system, whether that means bypassing immunity from a past coronavirus infection or from vaccination. However, vaccine experts say that a variant that would entirely evade vaccines is pretty improbable.

Every single coronavirus variant of concern that we’ve encountered so far has responded to the vaccines in some capacity. And the variants that have posed more of a danger to vaccine-induced immunity (Beta, Gamma) have not become dominant on a global scale, since they’ve been less transmissible than Delta. Our vaccines are very good—not only do they drive production of anti-COVID antibodies, they also push the immune system to remember the coronavirus for a long time.

It’s also worth noting here that, so far, Omicron does not appear to be more likely to cause severe COVID-19 symptoms. Angelique Coetzee, chairwoman of the South African Medical Association, announced on Saturday that cases of the variant have been mild overall. Hospitals in South Africa are not (yet) facing a major burden from Omicron patients.

What can scientists do to better understand Omicron?

One thing I cannot overstate here is that scientists are learning about Omicron in real time, just as the rest of us are. Look at all the “We don’t know yet.”s in this thread from NYU epidemiologist Céline Gounder:

Gounder wrote that we may have answers to some pressing questions within two weeks, while others may take months of investigation. To examine the vaccines’ ability to protect against Omicron, scientists are doing antibody studies: essentially testing antibodies that were produced from past vaccination or infection to see how well they can fight off the variant.

At the same time, scientists are closely watching to see how fast the variant spreads in South Africa and in other countries. The variant’s performance in the U.K., where it was first identified on Saturday, may be a particularly useful source of information. This country is currently facing a Delta-induced COVID-19 wave (so we can see how well Omicron competes); and the U.K. has the world’s best genomic surveillance system, enabling epidemiologists to track the variant in detail.

How does Omicron impact vaccine effectiveness?

We don’t know this yet, as scientists are just starting to evaluate how well human antibodies from vaccination and past infection size up against the new variant. The scientists doing these antibody studies include those working at Pfizer, Moderna, and other major vaccine manufacturers. Pfizer’s partner BioNTech has said it expects to share lab data within two weeks, according to CNBC reporter Meg Tirrell:

If BioNTech finds that Omicron is able to escape immunity from a Pfizer vaccination, the company will be able to update that vaccine within weeks. Moderna is similarly able to adjust its vaccine quickly, if lab studies show that an Omicron-specific vaccine is necessary.

Even if we need an updated vaccine for this variant, though, people who are already vaccinated are not going back to zero protection. As microbiologist Florian Krammer put it in a Twitter thread: “And even if a variant vaccine becomes necessary, we would not start from scratch… since it is likely that one ‘variant-booster’ would do the job. Our B-cells can be retrained to recognize both, the old version and the variant, and it doesn’t take much to do that.”

What can the U.S. do about Omicron?

On Friday, the Biden administration announced travel restrictions from South Africa and neighboring countries. The restrictions take effect on Monday, but virus and public health experts alike are already criticizing the move—suggesting that banning travel from Africa is unlikely to significantly slow Omicron’s spread, as the variant is very likely already spreading in the U.S. and plenty of other countries.

At the same time, travel restrictions stigmatize South Africa instead of thanking the country’s scientists for alerting the world to this variant. Such stigma may make other countries less likely to share similar variant news in the future, ultimately hurting the world’s ability to fight the pandemic.

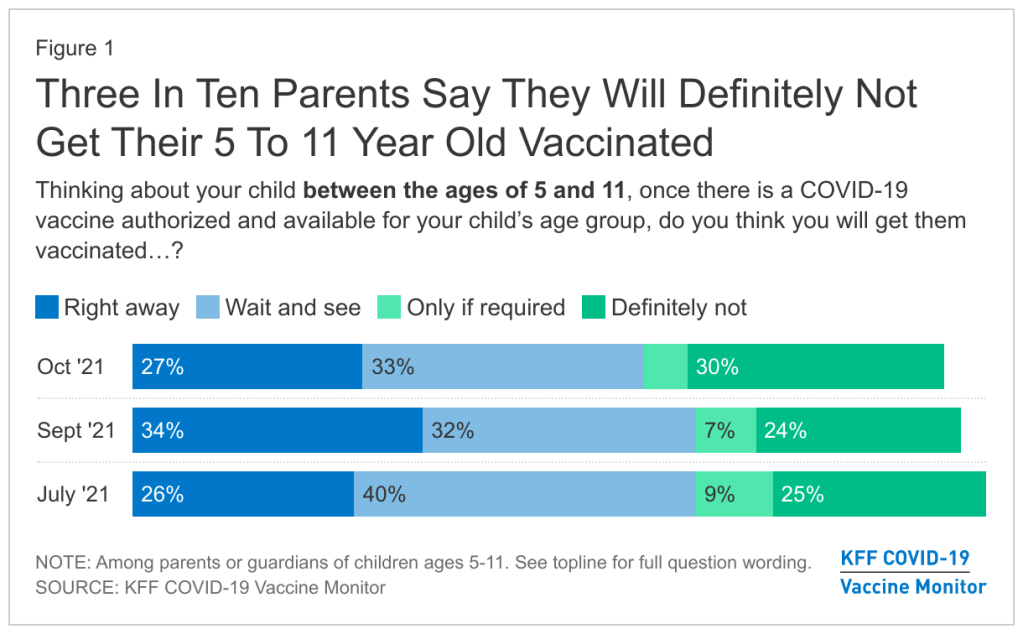

So what should the U.S. actually be doing? First of all, we need to step up our testing and genomic surveillance. As I mentioned above, Omicron can be identified from a PCR test; an uptick in PCR testing, especially as people return home from Thanksgiving travel, could help identify potential cases that are already here.

We also need to increase genomic surveillance, which could help identify Omicron as well as other variants that may emerge from Delta. In a post about the Delta AY.4.2 variant last month, I wrote that the U.S. is really not prepared to face surges driven by coronavirus mutation:

We’re doing more genomic sequencing than we were at the start of 2021, which helps with identifying potentially concerning variants, but sequencing still tends to be clustered in particular areas with high research budgets (NYC, Seattle, etc.). And even when our sequencing system picks up signals of a new variant, we do not have a clear playbook—or easily utilized resources—to act on the warning.

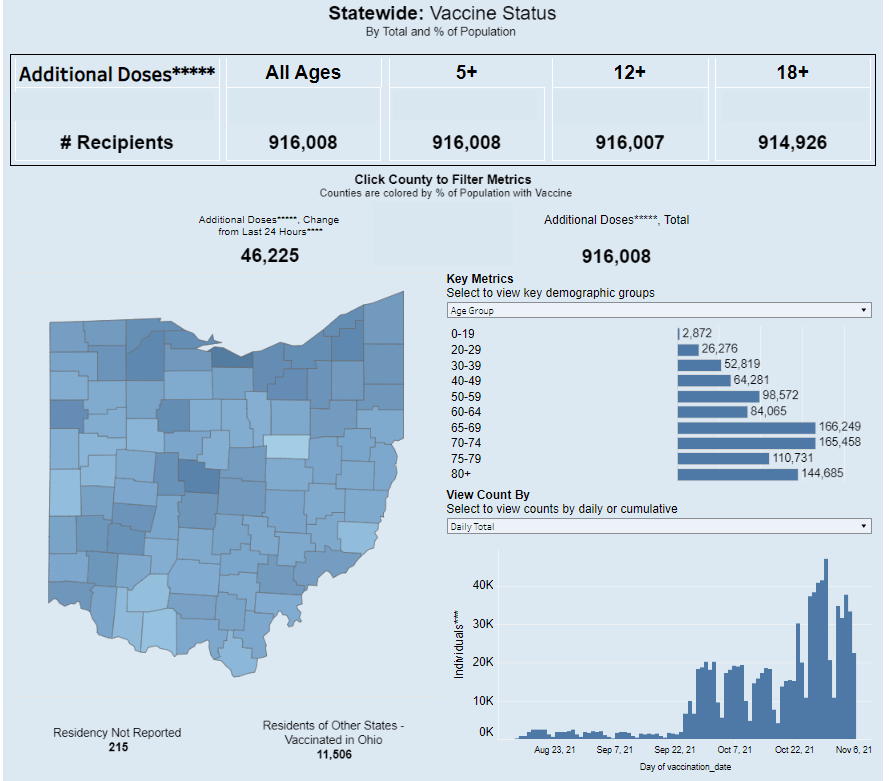

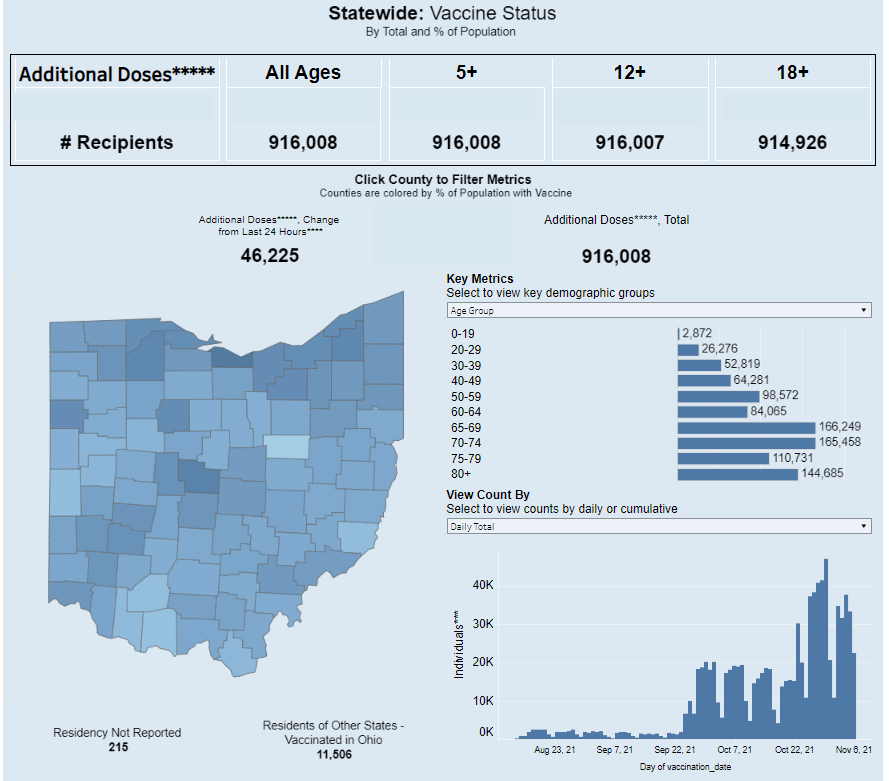

We also need to get more people vaccinated, in the U.S. and—more importantly—in the low-income nations where the majority of people remain unprotected. In South Africa, under one-quarter of the population is fully vaccinated, according to Our World in Data.

What can I do to protect myself, my family, and my community?

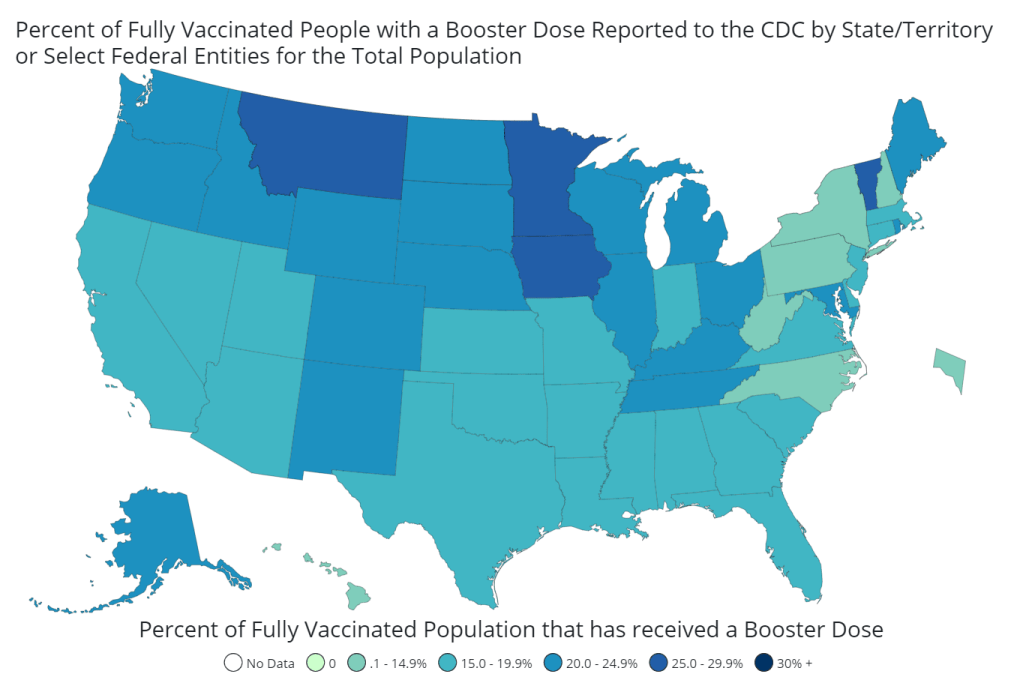

In general, do all of the same things that you’ve already been doing. Most importantly, get vaccinated (including a booster shot, if you’re eligible).

Also: Wear a mask in indoor spaces, ideally a good quality mask (N95, KN95, or double up on surgical and cloth masks). Avoid crowds if you’re able to do so. Monitor yourself for COVID-19 symptoms, including those that are less common. Utilize tests, including PCR and rapid tests—especially if you’re traveling, or if you work in a crowded in-person setting.

I’ve seen some questions on social media about whether people should consider canceling holiday plans, or other travel plans, because of Omicron. This is a very personal choice, I think, and I’m no medical expert, but I will offer a few thoughts.

As I said in the title of this post, we don’t yet know enough about this variant for it to be worth seriously panicking over. All of the evidence—based on every single other variant of concern that has emerged—suggests that the vaccines will continue to work well against this variant, at least protecting against severe disease. And all of the other precautions that work well against other variants will work against this one, too.

So, if you are vaccinated and capable of taking all the other standard COVID-19 precautions, Omicron is most likely not a huge risk to your personal safety right now. But keep an eye on the case numbers in your community, and on what we learn about this variant in the weeks to come.

What does Omicron mean for the pandemic’s trajectory?

This variant could potentially lead to an adjustment in our vaccines, as well as to new surges in the U.S. and other parts of the world. It’s too early to say how likely either scenario may be; we’ll learn a lot more in the next couple of weeks.

But one thing we can say right now, for sure, is that this variant provides a tangible argument for global vaccine equity. If the country where Omicron originated had a vaccination rate as high as that of the U.S. and other high-income nations, it may not have gained enough purchase to spread—into South Africa, and on the global path that it’s now taking.

As physician, virologist, and global health expert Boghuma Kabisen Titanji put it in a recent interview with The Atlantic:

If we had ensured that everyone had equal access to vaccination and really pushed the agenda on getting global vaccination to a high level, then maybe we could have possibly delayed the emergence of new variants, such as the ones that we’re witnessing.

I will end the post with this tweet from Amy Maxmen, global health reporter at Nature. The Omicron variant was a choice.