Longtime readers might remember that, back in August, I surveyed the available data on how COVID-19 is impacting American schools.

At the time, very few states were reporting school-specific data, even as school systems around the nation began to reopen for in-person instruction. In that early survey, I highlighted only Iowa as a state including district-level test positivity data on its COVID-19 dashboard. This dearth of data disappointed, but did not surprise me. There was no federal mandate for states, counties, or school districts to report such data, nor did the federal government compile such information.

There is still no federal mandate for school COVID-19 data, despite pleas from politicians and educators alike. So, as school systems across the country close out their fall semesters amidst a growing outbreak and prepare for the spring, I decided to revisit my survey. I sought out to find how many schools are reporting on COVID-19 cases in their K-12 schools, which metrics they are reporting, and how often. To get started with this search, I used the COVID Monitor, a volunteer effort run by Rebekah Jones which is compiling K-12 case counts from government sources and news reports.

Overall, many more states are providing school data now than in August. But the data are spotty and inconsistent; most states simply report case counts, making it difficult to contextualize school infections. (For more on why demoninators are important in analyzing school data, see my October 4 issue.)

You can see the full results of my survey in this spreadsheet (embedded below). But here are a few key findings:

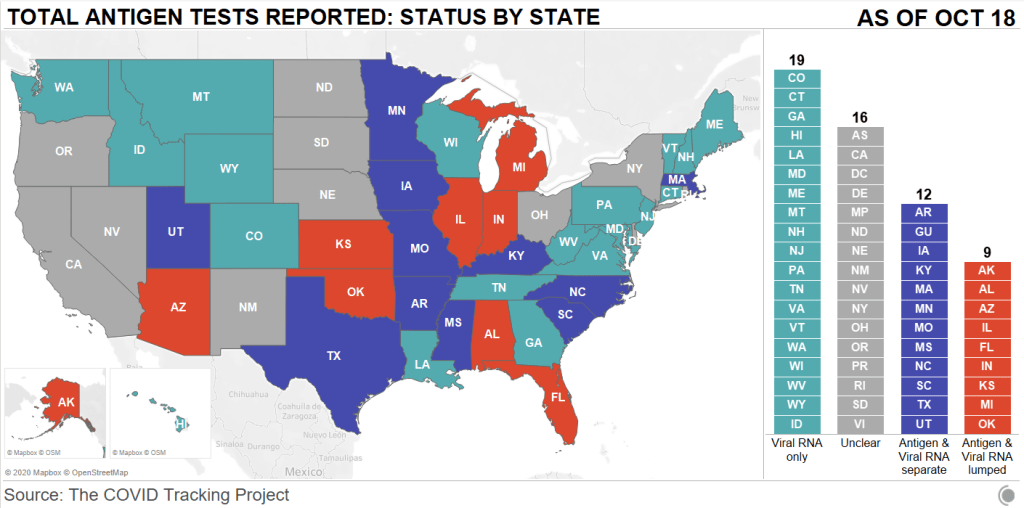

- In total, 35 states report case counts in all public K-12 schools. 6 states report in an incomplete form, either not including all schools or not including specific case counts.

- 9 states do not report school COVID-19 data at all. These states are: Alaska, California, Georgia, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and Wyoming.

- Most states update their school data either weekly or biweekly. Only 7 states update daily.

- Most states do not report counts of deaths and hospitalizations which are connected to school COVID-19 outbreaks. Only 5 states report deaths (Colorado, Kansas, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Virginia), and only 1 state reports hospitalizations (Kansas).

- Only 3 states report in-person enrollment numbers: New York, Massachusetts, and Texas.

- New York is the only state to report counts of COVID-19 tests conducted for K-12 students and staff.

And here are a couple of example states I’d like to highlight:

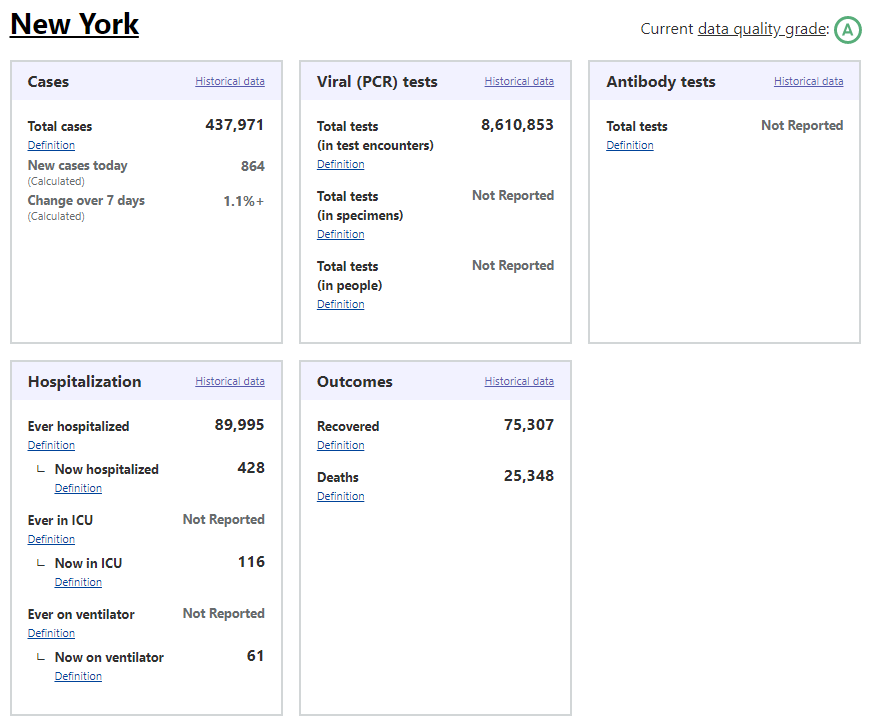

- New York has the most complete school data by far, scoring 19 out of a possible 21 points on my index. Not only does the state report enrollment and total tests administered to students and staff, New York’s COVID-19 Report Card dashboard includes the test type (usually PCR) and lab each school is using. Test turnaround times are also reported for some schools. This dashboard should be a model for other states.

- Indiana has a dashboard that I like because it is easy to find and navigate. You don’t have to search through PDFs or go to a separate dashboard—simply click on the “Schools” tab at the top of the state’s main COVID-19 data page, and you will see cumulative case counts and a distribution map. Clicking an individual school on the map will cause the dashboard to automatically filter. Indiana also reports race and ethnicity breakdowns for school cases, which I haven’t seen from any other state.

- Texas provides detailed spreadsheets with case counts and on-campus enrollments for over 10,000 individual schools. The state reports new cases (in the past week), total cases, and the source of school-related infections (on campus, off campus, and unknown). The infection source data suggests that Texas is prioritizing schools in its contact tracing efforts.

- Minnesota is one state which provides incomplete data. The state reports a list of school buildings which have seen 5 or more COVID-19 cases in students or staff during the past 28 days. Specific case counts are not provided, nor are specific dates on when these cases occurred. If I were a Minnesota parent at one of these listed schools, I’m not sure what I’d be able to do with this information beyond demand that my child stay home.

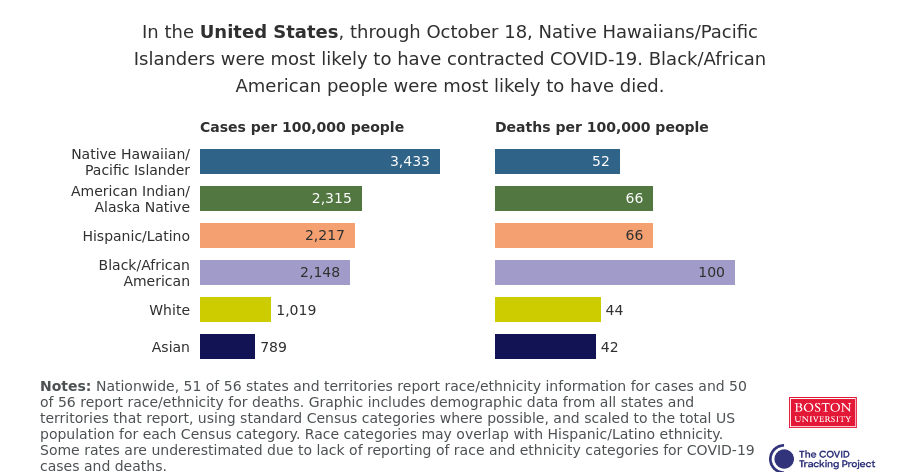

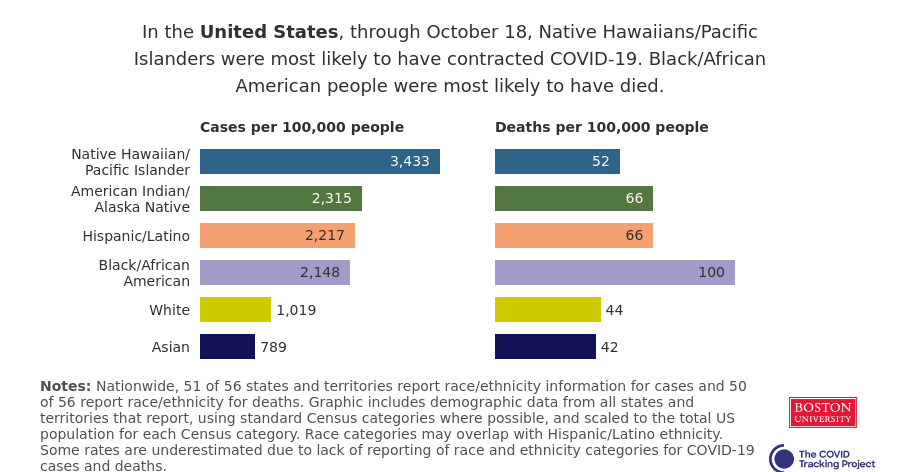

As cases surge across the country, more children become infected, and school opening once again becomes a heated debate from New York City to North Dakota, it is vital that we know how much COVID-19 is actually spreading through classrooms. How can we decide if school opening is a risk to students, teachers, and staff if we don’t know how many students, teachers, and staff have actually gotten sick?

Moreover, how can we understand the severity of this threat without enrollment or testing numbers? Reporting that a single school has seen three cases is like reporting that a single town has seen three cases; the number is worth very little if it cannot be compared to a broader population.

Volunteer sources such as the COVID Monitor and Emily Oster’s COVID-19 School Response Dashboard are able to compile some information, but such work cannot compare to the systemic data collection efforts that national and state governments may undertake. If you live in one of those nine states that doesn’t report any school COVID-19 data, I suggest you get on the phone to your governor and ask why.

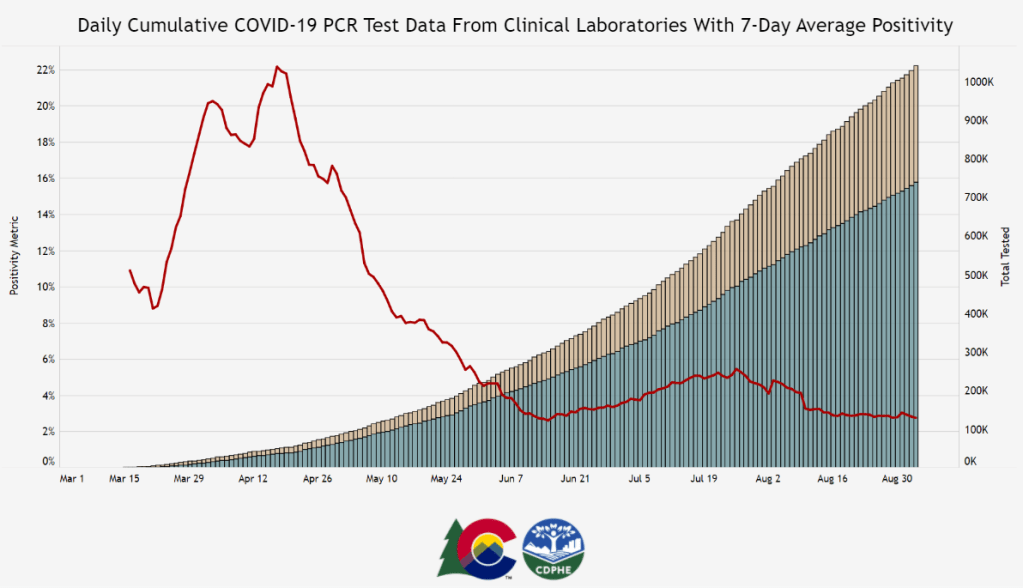

Also, speaking of New York City, here’s an update to the 3% threshold I reported on last week:

Here are the full results of my survey.

To use this for your own analysis, make a copy of the public Google sheet.