In December 2020, Congress provided the National Institutes of Health (NIH) with over $1 billion to study Long COVID. A couple of months later, the agency announced it would use this funding for an initiative called RECOVER: a large clinical trial aiming to enroll 40,000 patients, designed to answer long-standing questions about Long COVID and, eventually, identify potential treatments.

At the time, Long COVID patients and researchers were thrilled to see this massive investment. Long COVID patients may suffer from hundreds of possible symptoms, many of them debilitating; reports estimate that millions of people are out of work as a result of the condition. To anyone who has experienced Long COVID or talked to patients, as I have in my reporting, it’s clear that we need treatment options, and we need them yesterday.

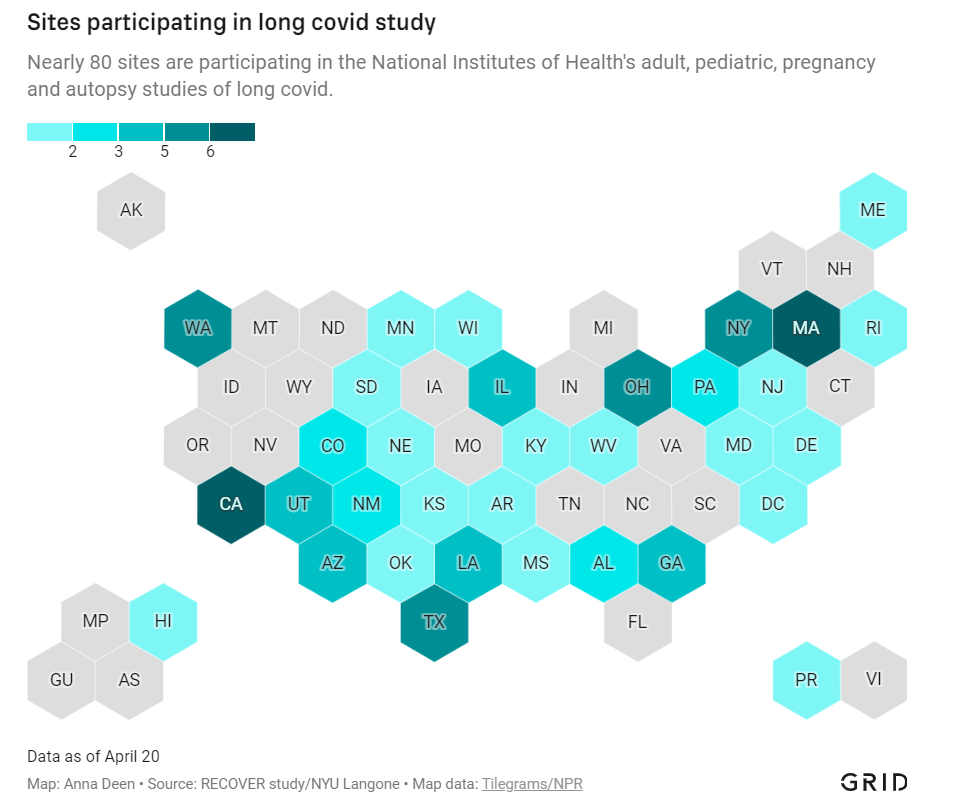

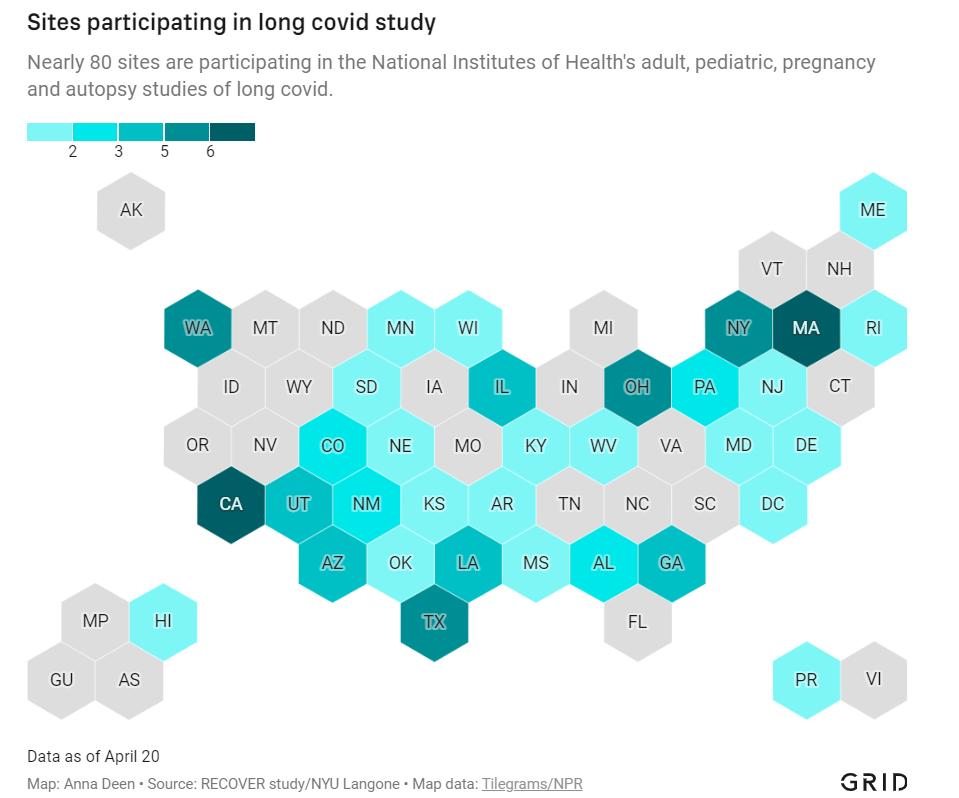

But that promising NIH study is floundering: it’s moving incredibly slowly (with treatment trials potentially years off); it’s enrolled a tiny fraction of the 40,000 patients originally planned; it’s failing to meet the needs of patients from the communities most vulnerable to COVID-19; and it has been critiqued by patient advocates on concerns of trial setup, transparency, engagement, inclusion of other post-viral illnesses, and more.

I explored the concerns around RECOVER for a story in Grid, published last Monday. My piece highlights critiques from patient advocates and Long COVID researchers outside of RECOVER, while also discussing some of the broader problems that make it difficult for an initiative like this to succeed in the first place.

In the COVID-19 Data Dispatch today, I’d like to dig deeper into those broader problems and share some material from my reporting for the Grid story that didn’t make it into the final piece. Here are five reasons why the U.S. is not set up for success when it comes to Long COVID research, based on my interviews and research for the piece.

The NIH is designed for stepwise research, not “disruptive innovation.”

One of my favorite quotes in the story comes from David Putrino, who directs a lab at Mount Sinai focused on health innovations and was one of the first scientists in the U.S. to begin focusing on Long COVID. Putrino described how the NIH’s usual mode of operation does not work when it comes to novel conditions like Long COVID:

“What the NIH does very well, better than most national research organizations around the world, is supporting research that slowly develops small innovations in scientific knowledge,” Putrino said. The agency normally supports series of stepwise trials, climbing from one tiny aspect of research into a condition or treatment to the next.

This method is good for “long-term innovations that take 20 years,” Putrino said, but not for “disruptive innovation.” Treatments for long covid fall into the latter category: higher-risk, higher-reward science that may be viewed as a waste of government funding if it doesn’t pay off.

The same day as my Grid story was published, last Monday, STAT News published a story by Lev Facher discussing an oversight board at the NIH that was supposed to improve efficiency at the agency… and has not met for seven years. While this story doesn’t discuss Long COVID specifically, it provides some pretty clear context for why a study like RECOVER—which is different from anything the agency has done before—may be hard to get off the ground.

Here’s the final quote in Facher’s story, from Robert Cook-Deegan, founding director of the Duke Center for Genome Ethics, Law and Policy:

“About every 10 years, the National Academies [of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine] are asked to review NIH, and they make recommendations, most of which are ignored,” he said. The agency’s “large, inertial, and ponderous bureaucracy,” he added, is “not terribly open to criticism as a whole.”

Clinical trials are difficult and time-consuming to set up, especially when they involve new drugs.

My story also discusses the red tape that U.S. researchers face when they attempt to test potential treatments on human subjects. For such a clinical trial, researchers need to get approval from an Institutional Review Board (or IRB), an oversight board that ensures a study’s design protects the rights and welfare of people who participate in the trial.

In the U.S., this approval can take months, and may have extra steps for government-funded research. Researchers in other countries often have much shorter processes, Lauren Stiles, president of the research and advocacy organization Dysautonomia International, told me. She gave the example of a researcher in Sweden studying a potential Long COVID treatment with funding from her organization: for this researcher, the equivalent of IRB approval took a few hours rather than a few months.

Clinical trials in the U.S. also face extra hurdles when they involve studying new drugs, as our research system makes it easier for companies that develop these drugs to do new clinical trials than for outside academics to undertake similar studies. For example, Putrino told me that he would love to study the potential for Paxlovid, the antiviral drug for acute COVID-19, to treat Long COVID patients. But, he said, “I physically don’t have the bandwidth to fill out the hundreds of pages of documents” that would be required for such a trial.

A recent story in The Atlantic from Katherine J. Wu focuses further on Paxlovid’s potential as a Long COVID treatment—and how hard it is to study. Quoting from Wu:

The company is “considering how we would potentially study it,” Kit Longley, a spokesperson for Pfizer, wrote in an email, but declined to clarify why the company has no study under way. That frustrates Putrino, of Mount Sinai, who thinks Pfizer will need to spearhead many of these efforts; it’s Pfizer’s drug, after all, and the company has the best data on it, and the means to move it forward… When asked to elaborate on Paxlovid’s experimental status, the NIH said only that the agency “is very interested in long term viral activity as a potential cause of PASC (long COVID), and antivirals such as Paxlovid are in the class of treatments being considered for the clinical trials.”

The NIH has historically underfunded and undervalued research into other post-viral conditions.

When I shared my Grid story on Twitter this week, a lot of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), dysautonomia, and other post-viral illnesses said that the issues outlined in my piece felt very familiar.

After all, the NIH has been failing to fund research into their conditions for decades. Pots, one type of dysautonomia, received less than $2 million a year in NIH funding before the pandemic, Stiles told me. As a result, scientists and clinicians in the U.S. have fairly limited information on these other chronic conditions—in turn, limiting the sources that Long COVID researchers may use as starting points for their own work.

Long COVID patients share a lot of symptoms with ME, dysautonomia, and other chronic post-viral illness patients; in fact, many Long COVID patients have been diagnosed with these other conditions. According to one study by the Patient-Led Research Collaborative, almost 90% of Long COVID patients experience post-exertional malaise, the most common symptom of ME.

Despite the historical underfunding, post-viral illness researchers have still made major strides in studying this condition that could provide springboards for RECOVER. But the NIH trial isn’t using them, say experts I talked to. Here are a few paragraphs from an early draft of the story:

“NIH is approaching Long COVID as a brand-new phenomenon,” said Emily Taylor, an advocate at Solve ME, even though it has extensive overlaps with these other conditions. “We’re starting at square one, instead of starting at square 100.”

Long COVID patients and those ME have already come together organically to share tips and resources, she said. For example, Long COVID patients versed in medical research have educated ME patients on potential biological mechanisms for their chronic illness, while ME patients have shared methods for resting, pacing, and managing their conditions.

Experts in conditions like ME were not included in the trial’s leadership early on, and are now outnumbered in committees by cardiologists, respiratory experts, and others who have limited existing knowledge about post-viral illness. “Right now, there are three people with [dysautonomia] expertise on these committees,” Stiles said.

With the other two experts, Stiles has advocated for autonomic testing—a series of tests measuring the autonomic nervous system, believed to be a key driver of Long COVID symptoms—to be conducted on all RECOVER patients. A few of these tests have been added to the protocol, she said, but not the full list needed to get a comprehensive reading of patients’ nervous systems.

America’s fractured medical system and lack of broad knowledge on Long COVID have contributed to data gaps, access issues.

How does a Long COVID patient know that they have Long COVID? Ideally, more than two years into the pandemic, the U.S. medical system would have developed a consistent way of diagnosing the condition. Instead, patients are still getting diagnoses in a variety of ways, including (but not limited to):

- A positive PCR test, followed by prolonged symptoms.

- A positive rapid/at-home test, followed by prolonged symptoms.

- Prolonged symptoms, perhaps later associated with COVID-19 via a positive antibody test.

- Self-diagnosis based on prolonged symptoms.

- An official diagnosis of Long COVID from a doctor.

- An official diagnosis of ME, pots, mass cell activation syndrome, and/or other conditions from a doctor.

Patients also continue to face numerous barriers to formal Long COVID diagnoses, compounded by the fractured nature of the medical system. A lot of doctors and other medical providers—especially at the primary care level—still don’t know about the condition, and may make it hard for patients to learn that their prolonged fatigue is actually Long COVID. PCR or lab-based COVID-19 testing is also getting harder to access across the country, and many doctors won’t take a positive antigen test as proof of infection.

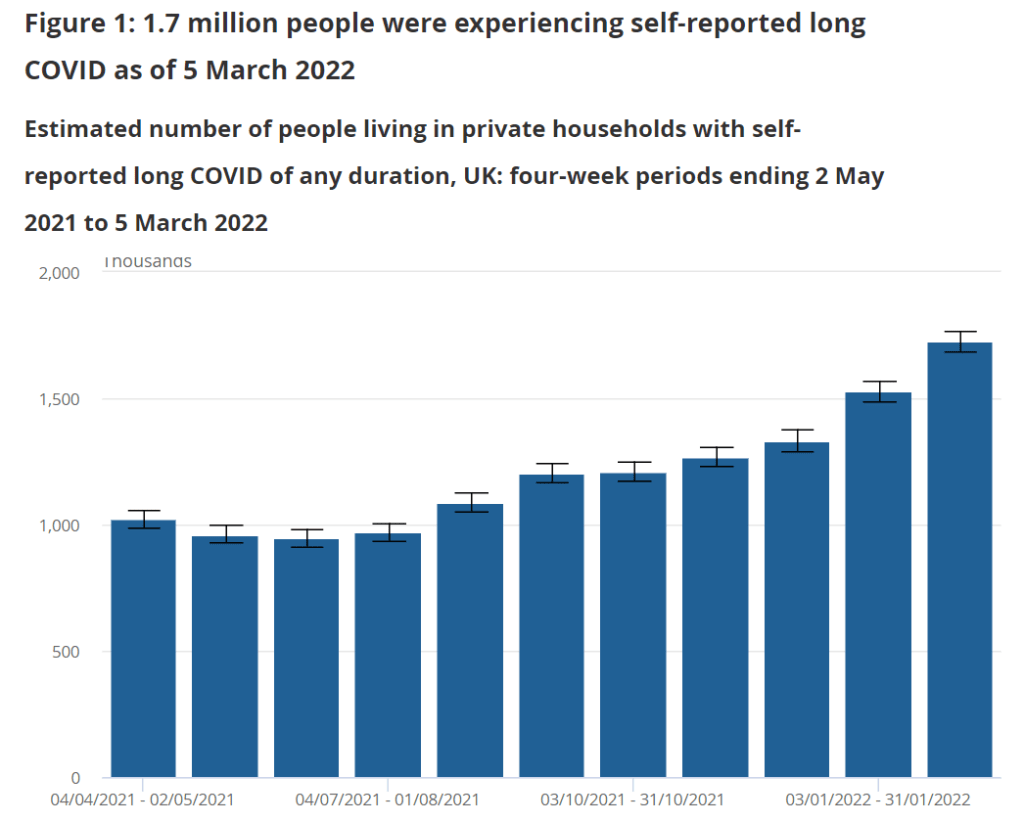

All of this means that the U.S. does not have a good estimate of how many Americans are actually suffering from Long COVID. There’s no central registry of patients who can be contacted for potential trials; there aren’t even basic demographic estimates of how many Long COVID patients are Black, Hispanic, or otherwise from marginalized communities. These data gaps make it hard for researchers studying Long COVID to set goals for patient recruitment.

And then, beyond receiving a diagnosis, actually getting care for Long COVID may require patients to wait weeks for appointments with specialists, contact many different doctors, and generally advocate for themselves in the medical system—while dealing with chronic, debilitating symptoms. As a result, as I wrote in the story:

The long covid patients who are believed by their doctors, who garner media attention, who serve on RECOVER committees — they’re more likely to be white and financially better-off, said Netia McCray, a Black STEM entrepreneur and long covid patient who has enrolled in the trial.

So far, RECOVER has not been doing much to combat this inherent bias in the patients who know about the trial (and about their own condition) and are able to sign up for participation.

Clinical trials in the U.S. are not typically set up in a way that prioritizes patient engagement, especially chronically ill patient engagement.

One major concern from Long COVID patient advocates involved with RECOVER is that the trial has not prioritized patient engagement—which should be a priority, considering all the medical bias that patients have faced while they’ve become experts in their own condition over the last two years.

Here’s a bit more detail on this issue, taken from an early draft of my Grid story:

Patients serving on the committees are dramatically outnumbered by scientists, creating an “intimidating” environment that makes it hard to speak up about their needs, said Karyn Bishof, founder of the COVID-19 Longhauler Advocacy Project. This feeling is exacerbated when scientists on the committees are misinformed about Long COVID and dismiss patients’ experiences, she said.

Some scientists on the committees are receptive to patient input, representatives told me. Still, the structure is not in their favor: not only are patents outnumbered, it’s also a challenge for them to simply show up to committee meetings. Many Long COVID patients are, by definition, dealing with chronic symptoms that are not conducive to regular meeting attendance. Some are managing a barrage of doctors appointments, jobs, caregiving responsibilities, and more.

For instance, a second patient representative on a committee with Lauren Stiles—who serves as a representative because she has suffered from Long COVID in addition to other forms of dysautonomia—once missed a meeting because she had to go to the hospital. “If I wasn’t there, no patient would have been represented at all,” Stiles said.

Patients are compensated for their time in meetings, but not for hours spent doing other research outside those calls. And there’s no structure for patient representatives to coordinate more broadly; patients are operating in silos, with limited information about what representatives on other committees may be doing.

The NIH has potential models for improving this structure; it could draw from past HIV/AIDS clinical trials that had oversight from that patient community, advocate JD Davids told me. And leaders of RECOVER have acknowledged that they need to improve: as I highlighted in the story, trial leadership met with patient advocates earlier this month to discuss potential changes:

[Lisa McCorkell, advocate and researcher from the Patient-Led Research Collaborative] said that the meeting made it clear that the NIH and RECOVER leadership understand that improving patient engagement is key to the study’s success. “We agreed to work together to strengthen trust, improve representation of patients, and ensure greater accountability and transparency,” she said in an emailed statement.

The pressure is on for the NIH and RECOVER leadership to follow up on their promises. I, for one, intend to continue reporting on the trial (and on Long COVID research more broadly) as much as possible.