This week, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) released a major report about the state of wastewater surveillance for infectious diseases in the U.S. The report, written by a committee of top experts (and peer-reviewed before its release), is an extensive description of the promise and the challenges of wastewater testing.

Its authors describe how a grassroots network of researchers, public officials, and wastewater treatment plant staff developed strategies for sewage testing, analysis, and communicating results. Now, as committee chair Guy Hughes Palmer writes in the report’s introduction, broader collaboration and resources are needed to “solidify this emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic into a national system” that continues to monitor COVID-19 as well as other public health threats. To this end, the report includes specific recommendations for the CDC’s National Wastewater Surveillance System.

Here are some key findings from the report, taken from its summary section and a NASEM webinar presentation last Thursday:

- Overall, the report finds that wastewater surveillance data “are useful for informing public health action and that wastewater surveillance is worthy of further development and continued investment.” The authors recommend that public agencies at all levels keep funding and promoting this monitoring tool.

- Wastewater surveillance is not a new technology; it’s been used for decades to monitor the spread of polio. But COVID-19 led to widespread adoption of this technology and innovation into how it could be used, driven by some municipalities and universities that were early to embrace wastewater.

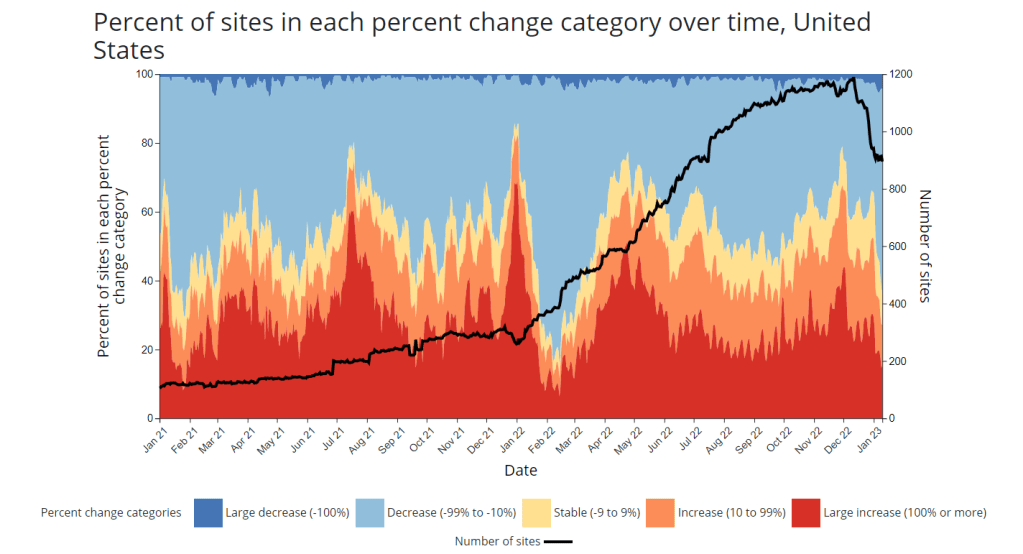

- As a population-level tool, wastewater surveillance provides data on how diseases spread through a community without relying on access to clinical testing. This surveillance is becoming more important for COVID-19 as people opt for at-home tests over PCR tests, and should be used specifically to track new variants.

- Community sewersheds that may be tested range in size from serving hundreds of people to serving millions; they also differ based on geography, demographics, and many other factors. As a result, early researchers in this space developed testing and analysis methods that were specific to their communities.

- Now, however, the CDC faces a challenge: “to unify sampling design, analytical methods, and data interpretation to create a truly representative national system while maintaining continued innovation.” In other words, standardize the system while allowing local communities to keep doing what works best for them.

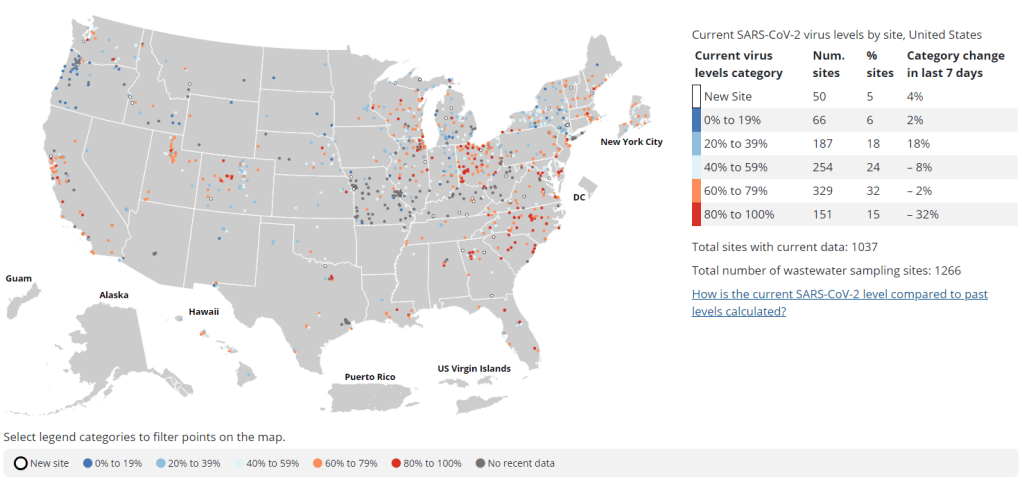

- Sites in the CDC’s National Wastewater Surveillance System (NWSS) are currently not representative of the U.S. as a whole, as the system is based on wastewater utilities and public health agencies choosing to participate.

- The CDC needs to expand this system to be more equitable across the country, with targeted outreach, offering resources to sites not currently participating, and other similar tactics. This expansion process should be open and transparent, the report’s authors write.

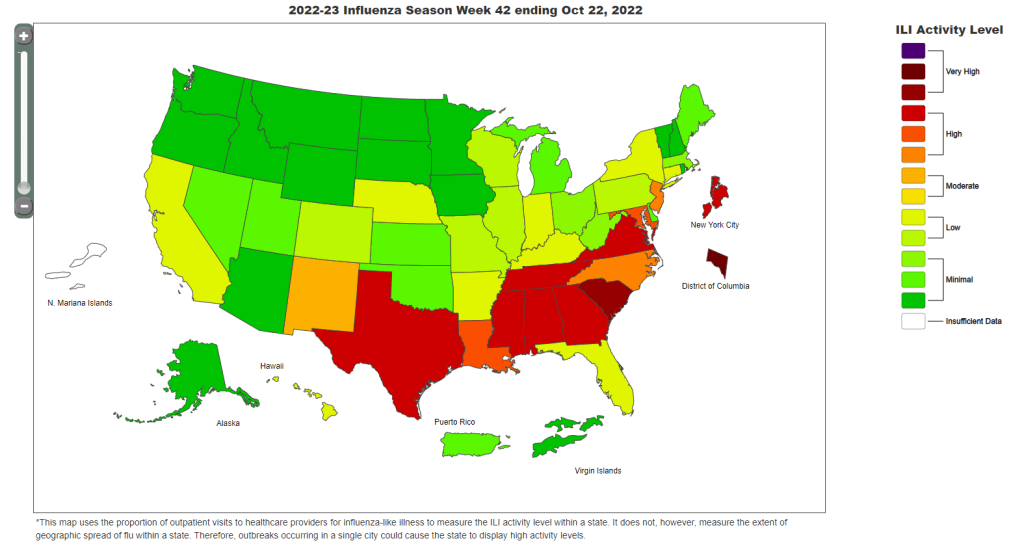

- As NWSS expands, the CDC should select and prioritize “sentinel sites” that can help detect new coronavirus variants and other new emerging health threats early on. These sites might include international airports as well as zoos and livestock farms, where potential animal-to-human transmission may be monitored.

- Better public communication is needed: the CDC (and other agencies) should improve its public outreach about wastewater data, including addressing any privacy concerns that people may have. The report specifically recommends that the CDC “convene an ethics advisory committee” to assist with privacy concerns and data-sharing concerns.

- In assessing potential new targets for wastewater surveillance, the report recommends three criteria: “(1) public health significance of the threat, (2) analytical feasibility for wastewater surveillance, and (3) usefulness of community-level wastewater surveillance data to inform public health action.”

- NWSS needs more funding from the federal government to expand its sites, continue its COVID-19 tracking efforts, fund projects at state and local levels, and pivot to new public health threats as needed. This funding needs to be “predictable and sustained,” the report’s authors write.

In related news: I just updated the COVID-19 Data Dispatch’s resource page for wastewater data dashboards in the U.S.

- The dashboard now includes information on four national dashboards, 24 state dashboards, seven local dashboards, and four regional dashboards.

- New states added in this update: Illinois (see last week’s source shout-out for more details), as well as Vermont and New Hampshire.

As always, please reach out if you see any errors on the page or would like to recommend a new source!